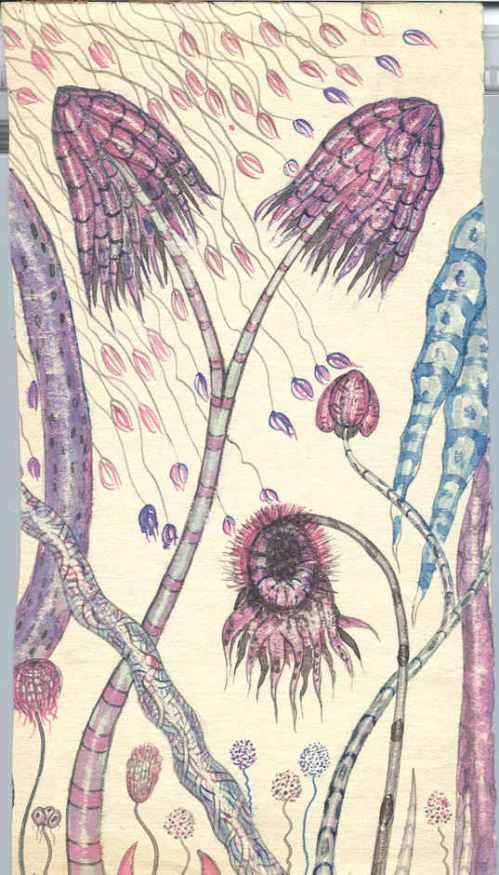

Clark Ashton Smith (1893 – 1961): Plants (Decade of the 1940s)

Orthosphereans have discussed the topic of synchronicity on several occasions. Synchronicity, a coinage of the psychologist Carl Jung, refers to the phenomenon of “lucky coincidences” or meaningfully convergent events. There are several orders of synchronicity. The one that I want to discuss in the following paragraphs is of a low order, but it serves to illustrate my conviction that we live, not merely in a physical world, but in a web of meaning whose source can only be immaterial – that is to say, spiritual. Events of a low order can arrange themselves, after all, in meaningful patterns. Patterning attracts the mind because patterning, at least in part, informs the mind, just as it informs the universe. Recently I posted at The Orthosphere my essay on “Eco-Music from Mahler to Rasmussen,” in two parts. “Eco-Music” means music permeated by the composer’s sense of the cosmos as a finely woven, complex pattern of spirit and body, temporality and spatiality, causality and spontaneity. I attempted to relate the compositional process of such artists to the visionary quest of the vates, seer, or shaman, who intercedes for the tribe in the realm of the sacred and on the home ground of the gods. When contemporary composers like John Luther Adams or Sunleif Rasmussen, express themselves in written word, they not only reveal their knowledge of the vatic tradition; they also reveal themselves as trying to communicate lore acquired on a level higher than the everyday, rather in the manner of an initiate in the mysteries. Listening to their music – which I did, intensely, over the period of accumulating the essay – convinced me of the validity of such statements.

Clark Ashton Smith (1893 – 1961): Spring Clouds (Decade of the 1940s)

My wont, since my retirement last May, is to write during daylight hours. Evenings I read, often while listening to music through headphones. Over the last couple of months I have set myself the task of re-familiarizing myself with two writers. One is the American poet Wallace Stevens (1879 – 1955); the other is the pulp fantasist and correspondent of H. P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith (1893 – 1961). Stevens was a New Englander, a graduate of Harvard and then of the New York School of Law. Smith was a Californian, who rarely traveled from his native Auburn, in Placer County. He barely graduated from high school and had no formal education beyond the secondary level. Although Smith began as a poet – and became known to an audience – his followers remember him as one of the prime contributors to Weird Tales and other specialty magazines of the 1920s and 30s. Smith typically set his tales in places to be found on no map – such as Atlantis, Hyperborea, and Zothique, which, according to the lore, either vanished eons ago or, as fictional constructs, will only exist eons in the future. Magic and wizardry pervade Smith’s fantasies, which exploit a Baudelairean vocabulary, with numerous Latinisms and archaisms, applied to a sense of grotesque irony in plot development and a prodigious imagination. Smith stopped writing narrative prose after 1937 and turned to drawing, painting, and sculpture. In these fields he maintained his focus on phantasmagoria. He vanished from memory in the decade after his death, but has enjoyed a resurgence of popularity since the 1990s. Smith has even been the subject of academic articles.

The Story. I own the collected stories and poems of Clark Ashton Smith in six volumes, but decided to resample his art in an anthology, A Rendezvous in Averoigne, published by Arkham House in 1988. Having completed the writing of “Eco-Music,” I settled myself on the couch in my man cave and opened the handsomely produced volume to a story entitled “The City of the Singing Flame,” which appeared in Wonder Stories for July, 1931. Unlike the typical Smith story, “The City of the Singing Flame,” is set contemporaneously in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Smith fashions for his readers a protagonist whose character and situation resemble his own. The story, with a brief foreword, consists of journal entries of one Giles Angarth, “whose fame as a writer of fantastic fiction was already considerable” on the eve of his sudden disappearance. Angarth has given the implied author of the foreword, one Philip Hastane, permission to publish the private record. Smith makes Angarth a loner, if not quite a recluse, and establishes his domicile in a remote cabin near “Crater Ridge” in the “Nevada Mountains.” “Crater Ridge,” Angarth writes in the first of the published journal entries, “lies a mile or less to the north of my cabin.” The Ridge, “though differing markedly in its character from the usual landscapes round about… is one of my favorite places.” He describes it as “exceptionally bare and desolate, with little more in the way of vegetation than mountain sunflowers, wild currant-bushes, and a few sturdy wind-warped pines and supple tamaracks.”

Angarth, a rather Lovecraftian surname, adds a few outlandish details: “Geologists deny it a volcanic origin; yet its outcroppings of rough, modular stone and enormous rubble-heaps have all the air of scoriac remains – at least, to my non-scientific eye.” Here and there the intuition must come to grip with forms “that suggest the fragments of primordial bas-reliefs, or small prehistoric idols and figurines.” Elsewhere among the debris there are rock faces “that seem to have been graven with lost letters of an indecipherable script.” On the day of the entry (“July 31st, 1930”), Angarth hikes to Crater Ridge to continue his exploration of its remoteness. He meanders among the outcroppings and mounds. He arrives in “a clear space amid the rubble, in which nothing grew – a space that was round as an artificial ring.” In the center of this “ring” stand “two isolated boulders, queerly alike in shape, and lying about five feet apart.” In his ornate sentences, Smith has invoked one of the recurrent themes of his oeuvre, a distinction between the puritanically scientific interpretation of phenomena and the vatic impression of intelligible order or of its traces. Smith plays with another recurrent theme, that of a temporality which exceeds the known historical chronology. Smith would have appreciated the work, say, of Graham Hancock, who makes the argument for archeological deep time and points to features of the landscape around the world that appear to him architectural rather than natural, but are identified as natural by the supercilious bevy of esteemed professors, all enjoying tenure.

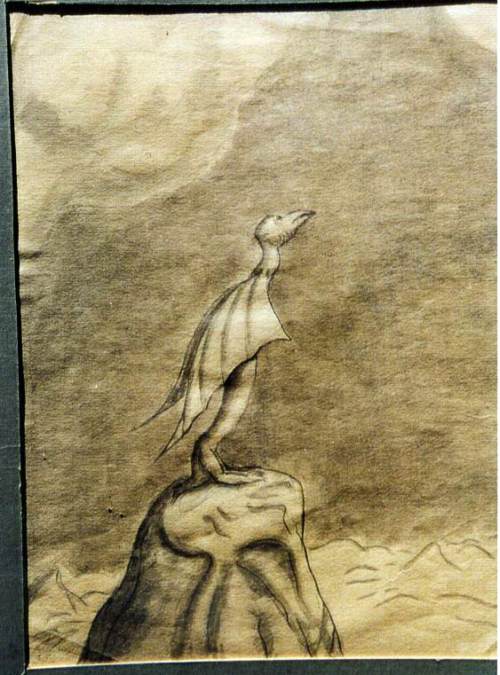

Clark Ashton Smith (1893 – 1961): Aspiration (Decade of the 1940s)

A dozen speculations run through Angarth’s mind. His “imagination was excited,” as Smith writes. The speculations pale, however, in comparison with what befalls Angarth when he takes “a single step forward in the vacant space immediately between the two boulders.” The event outstrips the capacity of language to convey it: “I seemed to be going down into an empty gulf… There was a feeling of intense, hyperborean cold; and an indescribable sickness and vertigo possessed me, due, no doubt, to the profound disturbance of equilibrium.” When Angarth recovers his balance, he finds himself in an alien landscape. He experiences a “ghastly sense of separation from all the familiar environmental details that give color and form and definition to our lives and even determine our very personalities.” In tackling the reading prerequisite to writing the “Eco-Music” essay, I delved into the Fourteenth Century book of Christian mysticism, The Cloud of Unknowing, a literary item from whose pages composer John Luther Adams has taken inspiration. The Cloud author returns constantly to the inadequacy of language in depicting “contemplation,” or communion with things transcendental, all the way up to God. The Cloud author also stresses the aspirant’s need to isolate himself from human commerce, so as to concentrate on the signs that direct his way on the visionary path. Smith’s protagonist lives something of a hermetic life, in the foothills, away from commerce, with forays into the mountains. He is a natural aspirant in the mystic way.

Adams the composer, in addition to his respect for the Neoplatonism of The Cloud of Unknowing, admires the sacred practices of the Aleuts, Inupiats, and Athabascans, whom he came to know during his four decades of life in remote areas of Alaska. As best he can, Adams tries to bring to his music the visionary acuity associated with the tribal shamans of the sub-polar Arctic. Adams – and in this he resembles Smith – suspects that modern people, in embracing a stubbornly utilitarian view of existence, have cut themselves off from the sources of spiritual nourishment and sacred admonition. They value safety over adventure. These thoughts, too, struck me as I read Smith’s “City of the Singing Flame.” In his first foray into the unknown world, Angarth lets caution prevail. After a brief reconnaissance he retraces his steps to the two megaliths and advenes once again in the familiar, but desolate, tract of Crater Ridge. He records in his journal what he has glimpsed: “A long, gradual slope covered with violet grass and studded at intervals with stones of monolithic size and shape.” He remarks also in the distance “a city whose massive towers and mountainous ramparts of red stone were such as the Anakim of undiscovered worlds might build,” with “wall beetling on wall.” The scene intensifies and focuses the picture of hoary ritual architecture intimated already by the boulder-detritus of the “Nevada Mountains” ridgeline. The event leaves Angarth “shaken.” Readers may take this to mean that Angarth’s dislocation has knocked his assumptions askew. A new phase of introspection has become necessary.

Reviewing his experience, Angarth permits allure gradually to overcome caution. He will return. During his second foray (August 3rd), instead of holding back he boldly passes between the two stones. Once on the other side, he foots a stone-paved track leading to the city, although he keeps to the side whence he can take refuge quickly in the trees and chaparral. He has caught sight of “singular entities,” but these ignore him as they pass. They too travel in the direction of “the severe architecture of the Cyclopean buildings.” He describes the directionless amber light that casts no shadow, and a pervasive silence. As he approaches the city, however, awareness overtakes him of a novel sensory stimulus. “There was a queer thrilling in my nerves,” Angarth writes, “the disquieting sense of some unknown force or emanation flowing through my body.” This “vibration” resolves, suddenly, into “music.” It clearly broadcasts itself from the “Titan city” that looms afar. In a mythic pattern, “the melody was piercingly sweet and resembled at times the singing of some voluptuous feminine voice,” whose “perpetually sustained notes… somehow suggested the light of remote worlds and stars translated into sound.” Smith makes reference to Homer’s sirens and to “a slow, drug-like intoxication of brain and senses.” At the same time, “the music conveyed the ideas of vast but unobtainable space and altitude, of superhuman freedom and exultation.” What has this to do with my invocation of synchronicity?

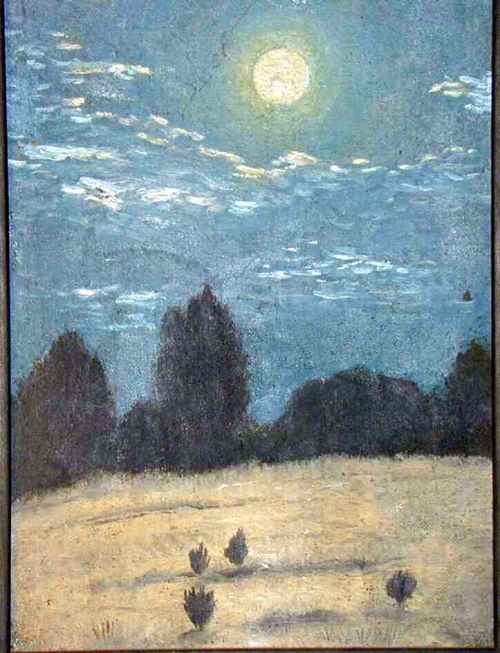

Clark Ashton Smith (1893 – 1961): Dreamland (Decade of the 1940s)

The “Eco-Music” essay quoted Mircea Eliade’s Shamanism (1951) on the topic of music. Eliade accords music a central place in ritual and would derive secular music from sacred music. Recently, on impulse, I drew Frederick Turner’s Beauty – the Value of Values (1991) from the shelf and, flipping through the pages, came to the chapter on “Neurocharms.” In Turner’s exposition of kallistics, or the philosophy of beauty, neurocharms function to raise the human susceptibility to aesthetic provocation – and this heightening of keenness in its turn increases apperception or the consciousness of higher levels of being. Among the neurocharms Turner lists “musical meter, tempo, and rhythm” and “musical tone, melody, and harmony.” “Rather interestingly,” Turner writes, “the capacity for musical performance seems to match the capacity for visual representation and picture-making.” In the chapter on “Beauty and the Anima Mundi,” Turner ties beauty “to the continuation of the process of creation.” To create beauty, or simply to cultivate it, is for Turner to imitate the Great Creative Principle that gave rise primordially to the cosmos. Smith understood these things explicitly, having schooled himself as a poet on the verse and prose of Charles Baudelaire. Belletristics counts Baudelaire as the originator of the Symbolist school of poetry, in which the transcendent connotations of the moniker strongly assert themselves.

Back to Smith’s story: On the third foray (August 5th), Angarth enters the city to take in “the measureless Babel of its buildings, of its streets and arcades.” He encounters for the first time the civic people, who are distinct from the “singular entities.” Among the traits that he lists are their “hieratic” attitude and “the opaque, jet-like orbs of their huge eyes… as impassive as the carven eyes of androsphinxes.” He follows the trail of “that remote, ethereal, opiate music.” It reverberates from “a temple-like building” rearing up in the center of “a great square.” Many species – all of them presumably sentient – throng the square, waiting to cross the threshold of its “many-columned entrance.” Angarth draws nigh to the object that serves for the narrative’s archemetaphor. In an inner sanctum of “immense, indefinite scope” comes into view “a circular pit above which seemed to float a fountain of flame that soared in one perpetual, slowly lengthening jet. This flame was the sole illumination; and it was also the source of the wild, unearthly music.” Angarth “felt the voluptuous lure and the high, vertiginous exaltation.” It was “pure as the central flame of a star.” When wariness overrides an impulse to unite with the fiery geyser, he backs away. But the same impulse conquers the shyness of numerous others, who “sprang forward and immolated themselves.”

On the fourth foray (August 13th), Angarth brings a friend, Felix Ebbonly, a commercial artist who has illustrated a number of his stories. Angarth wants corroboration for himself as much as for anyone else. Ebbonly proves willing to bear witness to whatever exotic happenings might occur. When Angarth has briefed Ebbonly they climb to Crater Ridge and pass through the portal. On broaching the city wall, Angarth reports, “my companion was in a veritable rhapsody of artistic delight.” The music, however, produces in Ebbonly “an ecstatic inward absorption,” in which talkativeness leaves him and he goes on in a somber hush. When they enter the presence of the Singing Flame, Ebbonly acts as though “wholly impervious to anything but the lethal music.” Ebbonly “ran forward in a series of leaps that were both solemn and frenzied, like the beginning of some sacerdotal dance, and hurled himself headlong into the flame.” Angarth admits to initial horror, but this state of shock swiftly diminishes: “I found myself envying my companion’s fate, and wondering as to the sensations he felt in that moment of fiery dissolution.” He pens a final note to his readers: “Tomorrow I shall return to the city.”

Clark Ashton Smith (1893 – 1961): Moonlight on Boulder Ridge (Decade of the 1940s)

The Assessment. At the end of “City,” Smith, ingeniously, leaves the most pertinent questions unanswered. Has Angarth led his friend, unwittingly, to make a sacrifice of himself in a primitive rite of blackly false transcendence? Is Angarth consequently guilty of manslaughter, which he will compound by suicide? Should readers despise him? Or is the Singing Flame another portal that opens on a new stage of a dangerous journey? Smith wrote many stories about explicitly sacrificial events set in cultish worlds whose gods, so-called, are bloody idols, and where consummation equals murder, not transfiguration. “City” is not one of them. For one thing, Angarth’s motive is curiosity; he inclines naturally to exploration and discovery. In Smith’s sacrificial stories, the central figure responds to vices like greed, lechery, libido dominandi, or a combination of all three. He acts arrogantly as he advances, stage by stage, to his just desert. The stage-by-stage pattern prevails in “City,” but of greed, lechery, or libido dominandi, Angarth’s character lacks any trace. Smith’s nefarious ones want to ensconce themselves in the center of the secular order where they plan to wield the murderous power of the demons. At the beginning of “City,” readers find Angarth already living on the margin, with no desire, but rather an aversion, for the secular center. In the nasty stories, Smith makes sure that ugliness taints all. In “City,” an eerie beauty pervades the other world. Turner, in Beauty, comments on the marginality of the beautiful: “Beauty always exists at some border or terminus of the world. Though it has no lack in itself, its natural place is at the edge of the great lack, the great precipice of the world, where past being abuts upon what is not, not yet.”

Another question concerns the archemetaphor of the Flame: Is it death? Eliade, in Shamanism, supplies knowledge that suggests the contrary. Or that suggests a poignant ambiguity. The shaman rises to his station by dint of overcoming an initiatic ordeal – or rather an arduous series of such ordeals. The initiant’s simulated demise belongs to this series, sometimes in several iterations. A Yakut informant told Eliade that, “as a rule, the future shaman ‘dies’ and lies in the yurt for three days without eating or drinking.” In shamanic initiation, the willingness to face what seems deadly correlates with “an unusual capacity for ecstatic experience.” Among the Yakuts, again, must face immolation, for the flame “of whatever kind, transforms man into spirit.” The candidate must submit to being branded or even burned as one of the requirements of his matriculation. A shaman acts, among his other offices, as the communal lore-bearer and rhapsodist. What else is Angarth? Eliade would even derive lyric poetry (and Smith, himself, was a lyricist) from shamanic “euphoria.” Eliade writes: “In preparing his trance, the shaman drums, summons his spirit helpers, speaks a ‘secret language’ or the ‘animal language,’ imitating the cries of beats and especially the songs of birds”; and “he ends by obtaining a ‘second state’ that provides the impetus for linguistic creation and the rhythms of lyric poetry.” Turner argues similarly in his discussion of neurocharms.

One can derive a similar and even rather disturbing argument for the Flame-as-portal from, of all things, The Cloud of Unknowing, that volume of Christian mysticism. The Cloud author admonishes the aspirant, in A. C. Spearing’s translation, to “break down all knowledge and feeling of every created being, but most forcibly of yourself.” The Cloud author presses his point: “For knowledge and feeling of all other created beings depends on knowledge and feeling of yourself, since, in comparison with yourself, all other beings are easily forgotten.” The major obstacle standing between the contemplator and God is the contemplator himself. It follows then, by the strict logic to which the Cloud author adheres, that, regarding “a naked knowledge and feeling of your own existence… that knowledge and feeling always needs to be destroyed.” The “Cloud of Forgetting” precedes the “Cloud of Unknowing” in the progress towards contemplation. It is perhaps significant that in Smith’s story, no one in the other world speaks. Knowing God, in the context of The Cloud, means entering the domain of paradox, for knowledge of the Ultimate, the One, never fits in language. Knowing in the exalted sense is unknowing. Elsewhere in Christian mysticism, the Church Father Origen uses fire as a metaphor for God.

Clark Ashton Smith (1893 – 1961): Demon (Decade of the 1940s)

And now – back to synchronicity… Bibliophiles like me collect books and they therefore also collect knowledge. A bibliophile is likely to collect his library eclectically so that his knowledge of things will not be a specialist’s or a professor’s narrow knowledge outside of which nothing exists. What the bibliophile knows hovers in his mind, scattered and patternless, and mostly uncalled-on, a kind of starry background, usually unnoticed. Every book collector will have had the experience however of a single trivial event that suddenly resolves a constellation from out of the hitherto unshaped scattering of stars. And that event invariably makes the impression of being uncaused, a happy boon, an instance, however small, of galvanizing grace. Such a happening befell me two or three times in the last two months. A bizarre, almost misplaced flute-note buried in the complex texture of the fanfare-ritornello in the first song of Gustav Mahler’s Lied von der Erde suddenly struck me – and I must have listened to Das Lied a hundred times over the decades – as significant or at least significantly placed. This sudden standing-out of a single note in a complicated orchestral texture exerted a ripple-effect. The texture itself suddenly became an object of attention. Just as suddenly, it occurred to me that it was possible to think of an orchestral score in analogy with a biome, a living environment in which every part is connected dynamically to every other part and all the parts subordinated, again dynamically, in a non-mechanical, a living whole.

On thinking that, I recalled my glancing acquaintance with a number of contemporary composers who espouse an ecological view of things and purport to embody that view in the deep-structure of their work. (Someone has to take cognizance of these things, after all.) I sought out those works, listened to them repeatedly and intently, compared them to other compositions that I already knew – and the result was the “Eco-Music” essay, into which any number of sub-topics sneakily entered, such as shamanism and initiation. But even before any inkling of the essay nodded to me, I had, as I have previously written, begun a review of the poet Stevens and the pulp-writer Smith. On the evening when I had put the finishing touches on the “Eco-Music” essay, I had come to “An Ordinary Evening in New Haven” in the Stevens-anthology and to “The City of the Singing Flame” in the Smith-anthology. It was unplanned. I was merely following the table of contents in both cases. Parenthetically, it strikes me that Stevens and Smith have a lot in common and that the themes of “An Ordinary Evening” and those of “The City” are remarkably convergent, but I omit to undertake the comparison herein. Perhaps this choice – of Stevens and Smith – belongs, of itself, to synchronicity. I might have selected Virginia Woolf or Ray Bradbury or Martin A. Hansen, but I selected Smith or maybe he selected me. Or something – neither Smith nor I – selected us both for confrontation in that uncanny moment in the stirrings of the Weird. And in no moment of this train of psychic events, with its effect of knocking my assumptions askew, was I thinking of myself!

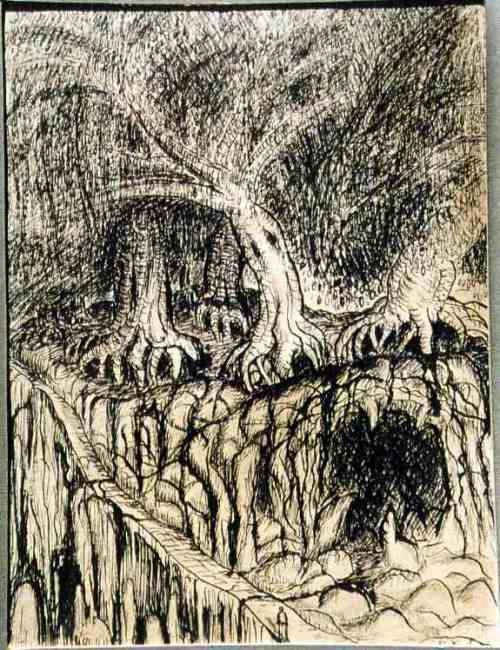

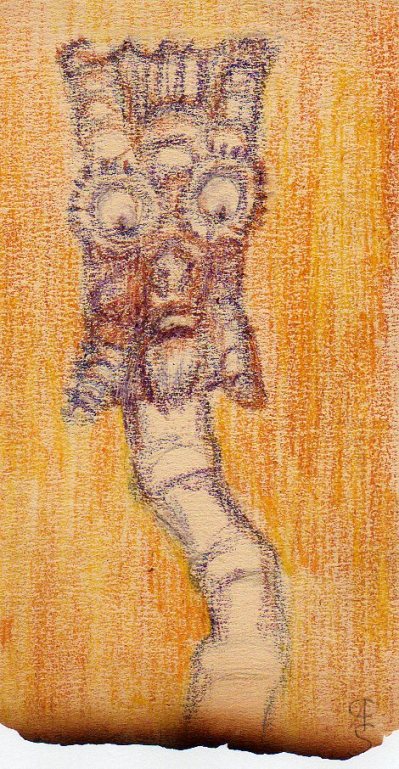

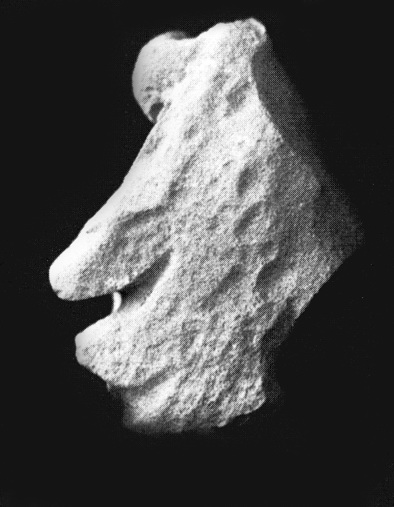

Clark Ashton Smith (1893 – 1961): Crater Ridge Pseudo-Sculpture (Decade of the 1950s)

A Note on the Gallery. Smith illustrated and sculpted his lifelong, but the archive of his pencil drawings, watercolors, and sculpted miniatures seems to date from the time he left off writing stories, at the end of 1937, through to his death in 1961. (He went on writing verse.) Few if any of the plastic items that Smith bequeathed to posterity carry a date. It is only possible to attribute them to the 1940s and 50s. In some cases, Smith links a drawing, painting, or sculpture through its title to one of his stories. An example is his deliberately primitive bust bearing the name of “Crater Ridge Pseudo-Sculpture,” a reference to “The City of the Singing Flame.” It looks like an idol from the Stone Age. In his proclivity to the plastic arts, Smith resembles or more accurately anticipates another contributor of fantastic fiction to the mid-Twentieth Century pulp magazines, Richard Sharpe Shaver (1907 – 1975). Shaver came to public notice when Editor Ray Palmer published I Remember Lemuria in Amazing Stories in 1945. Smith probably influenced Shaver, but Shaver, fascinating though his work is, wrote at a much lower level of artistic integrity than Smith. Shaver promulgated the “Dero Conspiracy.” Deros (“Detrimental Energy Robots”) are hangers-on from a vastly ancient Demonic regime that once tyrannized the human race only to suffer cosmic punishment. Deros live in subterranean caverns which exist everywhere and lead to the abandoned cities of the Demons. All misery comes from the Deros, who specialize in kidnapping innocent victims and torturing them in their deeply buried dungeons. Shaver was clinically diagnosed with paranoia and spent time in an asylum. Smith, by contrast, seems to have been remarkably compos mentis. He accepted his situation of dignified poverty and of working as a handyman in Auburn and its vicinity. He even married at the late age of sixty years. Smith’s drawings and paintings, in particular, have a humorous quality missing in Shaver’s drawing and paintings.

Dr. Bertonneau,

Thank you for this post. My own feeble synchronicity is that I have recently purchased Wallace Stevens’s collected poems – I have never read him, but am enough of a Harold Bloom fan to have been persuaded – and am currently reading through the collected works of Lovecraft published – beautifully – by Arkham House press. I have now purchased through them the Smith collection you reference here. Thanks again and looking forward to reading Smith.

I have a very good memory of sitting in a cabana overlooking a beach in Puerto Rico, at the age of twenty-three, reading Wallace Stevens and sipping cold beer. My taste for Stevens may have gone the way of my taste for beer and beach cabanas, but the memory is still sweet.

That is a remarkably Stevensian sentiment!

I love Smith’s prose. You might take a paragraph at random from any of the stories and you could make a long list of the felicities — those of vocabulary, syntax, figure, and other “neurocharms,” as Frederick Turner calls them. Smith’s poetry is also worth a gander. Both Stevens and Smith are American Symbolists, taking their starting cues from Charles Baudelaire and the French Symbolist school that he inspired. I predict that there are many synchronistic delights in store for you as you read your way through A Rendezvous in Averoigne.

Pingback: Clark Ashton Smith’s “City of the Singing Flame” & Synchronicity | Reaction Times

Pingback: City of the Singing Flame | TENTACLII : H.P. Lovecraft blog

Pingback: Clark Ashton Smith’s Representation of Evil – The Orthosphere

Pingback: Under the Iron Dome: Thomas Bertonneau on Transcendence – The Orthosphere