[Note: This essay appeared some few years ago in the Sydney Traditionalist Forum, shortly after the death by suicide of its subject. The work of Venner remaining relevant, I re-post the essay here, with a few small changes.]

Dominique Venner (born 16 April 1935) ended his life publicly and dramatically by shooting himself in the mouth before the altar of Our Lady of Notre Dame in Paris six years ago on 21 May 2013. The bullet passed through Venner’s brain and exited the back of his head. In the opening paragraph of a suicide note that he sent to his publisher, Venner sought to justify his action:

I am healthy in body and mind, and I am filled with love for my wife and children. I love life and expect nothing beyond, if not the perpetuation of my race and my mind. However, in the evening of my life, facing immense dangers to my French and European homeland, I feel the duty to act as long as I still have strength. I believe it necessary to sacrifice myself to break the lethargy that plagues us. I give up what life remains to me in order to protest and to found. I chose a highly symbolic place, the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris, which I respect and admire: She was built by the genius of my ancestors on the site of cults still more ancient, recalling our immemorial origins.

A reader cannot avoid remarking the contradictions in Venner’s testament. A professed love of life comports itself awkwardly with a gesture of self-annihilation. One could argue that Venner meant by “life,” not his own, but the collective, trans-personal vitality of his children and their descendants; he refers after all to “the perpetuation of [his] race and [his] mind.” Seen in that way, his suicide might rise to being a Stoical demonstration, like those of Petronius and Seneca in the time of Nero. Even so, no few problems remain; not least the dis-relation between Venner’s professed respect and admiration for the “highly symbolic place” of the Lady Church and his having blemished its consecrated precincts with his effluvia. How moreover would such an act “break the lethargy that plagues us”? More likely – even patently, looking back on the event – it would merely add to the pernicious confusion of the times. The explanation of these contradictions is undoubtedly linked to the fact that while Venner acknowledged his belonging to a specifically Christian civilization in its late phase, he never himself identified as an adherent of that faith. Like his countrymen-contemporaries Guillaume Faye (b. 1949) and Alain de Benoist (b. 1943), Venner espoused Friedrich Nietzsche’s Neo-Pagan view of Christianity as “slave morality,” a religion of defeat and death, and the cause of rather than the antidote to the malaise of modernity unleashed. Like Nietzsche, whom Venner admired, and who signed his last letters as “The Crucified One,” the suicide might well have been experiencing a revilement of Christ which was, at the same time, a desire to rival and replace Him. That would account for Venner’s characterization of his act as an instance of “self-sacrifice” and for his references to “cults still more ancient” than the Cult of the Virgin on the Ile de la Cité, with whose pre-Christian religiosity he would have identified in opposition to Christianity.

I. Despite all that, adherents and defenders of Christian civilization – or of a less creedal, “perennial” Tradition – will assuredly find in Venner’s suicide note a number of pithy assertions with which they can concur, despite a morally troubling context. Venner’s view of the reigning cultural degeneracy, for example, corresponds largely to theirs. Venner writes of his “protest against poisons of the soul and the desires of invasive individuals to destroy the anchors of our identity, including the family, the intimate basis of our multi-millennial civilization.” While invoking a type of cultural relativism, Venner nevertheless attests on behalf of a properly European culture that stands in rightful vigilance over its integrity. “While I defend the identity of all peoples in their homes,” as Venner writes, “I also rebel against the crime of the replacement of our people.” The word “crime” is strong enough to underscore itself. Claiming the absence of any “identitarian religion,” Venner emphasizes as the basis of Western consciousness what he calls “a common memory going back to Homer,” which he describes as “a repository of all the values on which our future rebirth will be founded once we break with the metaphysics of the unlimited, the baleful source of all modern excesses.” Christians and Traditionalists will recognize themselves in that pronouncement too, with its call for limitation rather than do-what-you-will. In a final sentence Venner hopes that his friends and survivors will find “in my recent writings intimations and explanations of my actions.”

I. Despite all that, adherents and defenders of Christian civilization – or of a less creedal, “perennial” Tradition – will assuredly find in Venner’s suicide note a number of pithy assertions with which they can concur, despite a morally troubling context. Venner’s view of the reigning cultural degeneracy, for example, corresponds largely to theirs. Venner writes of his “protest against poisons of the soul and the desires of invasive individuals to destroy the anchors of our identity, including the family, the intimate basis of our multi-millennial civilization.” While invoking a type of cultural relativism, Venner nevertheless attests on behalf of a properly European culture that stands in rightful vigilance over its integrity. “While I defend the identity of all peoples in their homes,” as Venner writes, “I also rebel against the crime of the replacement of our people.” The word “crime” is strong enough to underscore itself. Claiming the absence of any “identitarian religion,” Venner emphasizes as the basis of Western consciousness what he calls “a common memory going back to Homer,” which he describes as “a repository of all the values on which our future rebirth will be founded once we break with the metaphysics of the unlimited, the baleful source of all modern excesses.” Christians and Traditionalists will recognize themselves in that pronouncement too, with its call for limitation rather than do-what-you-will. In a final sentence Venner hopes that his friends and survivors will find “in my recent writings intimations and explanations of my actions.”

Defenders of Christian civilization and Traditionalists alike will point out that Christianity is nothing if not the historical “identitarian religion” of Europe, and that if modern people in their numbers had abandoned the Church the fault would lie with them at least as much as with the Church. In addition there is the fact that the High Medieval religiosity of Europe was a mélange of Pagan and Christian themes. The authors of the Grail Romances never ceased being Christian simply because they worked with mythic materials endowed on posterity by Celtic heathendom. Nor did Sandro Botticelli ever cease being Christian simply because he painted a startling Venus borne aloft from the sea waves on a fantastic scallop. Medieval zealots of the Church might have tried to extirpate vestiges of paganism, something concerning which Venner once issued a complaint, but the historical point is that the zealots failed. The Renaissance offers itself as the proof. While making the objections and pointing to the errors, Venner’s fideistic critics must yet acknowledge that, beyond its sniping and rather adolescent treatment of Christianity, Venner’s work, if not precisely the man himself, remains valuable to them – more valuable, say, than the work of Faye and Benoist, the considerable merit of their work notwithstanding. In the aftermath of Venner’s death, his achievement bears re-examination, not least because his life implicates the late Twentieth Century and its continuation in the Twenty-First.

Venner himself took on the role of chief recorder of his life. Many of his books and even his oeuvre, when taken whole, run to the autobiographical. A scrupulous reading must keep in mind then that Venner the subject plays Boswell to his own Johnson and that investigators therefore receive only a carefully controlled version of events. Yet he appears to hide nothing. He is frank about his participation in the Organisation de l’armée secrète in 1961, his subsequent conviction in a military court for crimes pertaining to his participation, and his eighteen-month sentence. Some OAS members received death-sentences and gave up their ghosts before a firing squad. The most famous living survivor of the OAS after Venner’s death is Jean-Marie Le Pen, founder of Le Front National and the father of Marine Le Pen. Concerning the OAS, in the autobiographical Shock of History (English translation 2015), Venner answers his interlocutor, Pauline LeComte, un-repentantly: “After two years of [army] service in Algeria, I wanted to continue the fight in the world of political agitation. I became convinced that the fate of Algeria would not be decided on the battlefield, but in Paris.” As Venner puts it, he helped to organize “a small political Free Corps that sought a kind of nationalist revolution.” The OAS sought to realize a coup-d’état against General De Gaulle’s Fourth Republic. On release from prison, Venner immediately re-entered politics, founding the group Action Europe, to which, he claims, “the New Right… owes of much its intellectual structure.”

Venner’s penchant for action, including a willingness to resort to armed violence, finds reflection in his gallery of heroes. Whom did Venner venerate? In Chapter 4 of Shock, “Hidden Heroic Europe,” Venner addresses the case of Claus von Stauffenberg, the would-be assassin of Adolf Hitler and the leading light of a failed coup-d’état against the Nazi regime. Venner asserts Stauffenberg to have been, not only “the most unwavering of Hitler’s adversaries,” but also a man of “high-born and noble” character who “believed that certain elite men were appointed to accomplish noble things.” In Venner’s description of the Valkyrie conspiracy, readers will detect its anticipatory parallelism, in Venner’s mind, with his own conspiratorial activity against the Fourth Republic. Venner reminds LeComte that Stauffenberg stemmed from the Swabian nobility and that among his motives his intense nationalism figured importantly. Venner reasonably rejects the notion that Stauffenberg acted in order to placate the “two Anglo-Saxon Thalassocracies.” Stauffenberg never, in fact, planned to dismantle the Reich; he wanted rather to purge it of National Socialism, while retaining the institutions of the Prussian State. Venner also remarks that Stauffenberg was an educated man who admired the Greeks and Romans and professed his admiration for Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, a statement that would assimilate the two men. One recalls the references to “a common memory going back to Homer” in the suicide note. One recalls also the reference to “cults still more ancient,” hence pre-Christian, hence legitimate where Christianity is not, in the same source. Did Venner think that his act would stimulate a revival of such religiosity? If so, it would be flawed thinking, as most modern people have no religiosity whatever and are unlikely to respond to esoteric cues.

Venner’s penchant for action, including a willingness to resort to armed violence, finds reflection in his gallery of heroes. Whom did Venner venerate? In Chapter 4 of Shock, “Hidden Heroic Europe,” Venner addresses the case of Claus von Stauffenberg, the would-be assassin of Adolf Hitler and the leading light of a failed coup-d’état against the Nazi regime. Venner asserts Stauffenberg to have been, not only “the most unwavering of Hitler’s adversaries,” but also a man of “high-born and noble” character who “believed that certain elite men were appointed to accomplish noble things.” In Venner’s description of the Valkyrie conspiracy, readers will detect its anticipatory parallelism, in Venner’s mind, with his own conspiratorial activity against the Fourth Republic. Venner reminds LeComte that Stauffenberg stemmed from the Swabian nobility and that among his motives his intense nationalism figured importantly. Venner reasonably rejects the notion that Stauffenberg acted in order to placate the “two Anglo-Saxon Thalassocracies.” Stauffenberg never, in fact, planned to dismantle the Reich; he wanted rather to purge it of National Socialism, while retaining the institutions of the Prussian State. Venner also remarks that Stauffenberg was an educated man who admired the Greeks and Romans and professed his admiration for Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, a statement that would assimilate the two men. One recalls the references to “a common memory going back to Homer” in the suicide note. One recalls also the reference to “cults still more ancient,” hence pre-Christian, hence legitimate where Christianity is not, in the same source. Did Venner think that his act would stimulate a revival of such religiosity? If so, it would be flawed thinking, as most modern people have no religiosity whatever and are unlikely to respond to esoteric cues.

Consider, finally, what Venner observes regarding Stauffenberg’s moral resolution: He carried out his part in the Valkyrie conspiracy despite his realistic assessment that the plan would probably fail. Stauffenberg was, as Venner puts it, “on a crucial mission of regeneration” for Germany; despite his failure to realize his aim, Stauffenberg’s “act of sacrifice on 20 July 1944 served to cleanse the German people from the blemish of the Führer’s regime.” Notice, however, what Venner omits to say about Stauffenberg: Namely that the officer and nobleman continued to be a practicing Catholic all his life. That is a blatant omission, even more so in that Venner rehearses the facts about Stauffenberg and Valkyrie for over a dozen pages. In Stauffenberg’s manifesto – which Venner quotes in full – readers will come across this sentence: “We [the conspirators] recognize the great traditions of our Western culture, a coalescence of Hellenic and Christian origins.” Venner makes no comment (the quotation of the manifesto in full concludes the chapter), but the reader is left wondering how he might have assimilated Stauffenberg’s recognition. He probably could not have done it. Not incidentally, another supporter of Valkyrie, General Erwin Rommel, also like Stauffenberg remained religiously active, in his case as an Evangelical Lutheran. Stauffenberg did not become a suicide: His executioners stood him against a wall and shot him. Rommel indeed resorted to suicide: With the Gestapo surrounding his house, he first conferred with his eldest son, and then retired to his study to end his life with a pistol-shot. Venner sides with Stauffenberg against Hitler’s Reich, but Stauffenberg opposed Hitler’s Reich in part because it was an atheistic-totalitarian polity that sought to subdue and abolish Christianity.

It is worth sorting out the differences further. When Venner killed himself he was not, as far as anyone knows, under external duress, but Rommel, whom Venner never mentions in The Shock, emphatically was. Venner’s hero Stauffenberg died by firing squad, not by his own hand. Venner, perhaps rightly, describes Stauffenberg’s death as a purifying “sacrifice,” the same description that he applies to his own suicide in advance. The description certainly gains plausibility in reference to Stauffenberg, but not so much in reference to Venner. The function of the description would once again be to assimilate the two men, to Venner’s benefit, but the gesture can only effectuate itself through the omission of Stauffenberg’s Catholicism. Venner rejects Christianity, including Catholicism, on Nietzsche’s arguments. Neither Stauffenberg nor Rommel subscribed to Nietzsche, but both practiced the Christian faith. Rommel’s suicide explains itself, and commands respect, in a way that Venner’s suicide cannot. Among Rommel’s motives, protecting his family from associative retribution by an enraged power must have figured largely; his act thus recommends itself as a grim concession to his wicked enemies, who, wicked though they were, indeed accepted the concession and left the family unmolested. Rommel’s wager proved its rationality in its sequel. Venner could stake a claim to no such motive as Rommel’s; and whether or not he had arranged for the welfare of his family, his act invites assessment as grossly privative and not a little bit nihilistic. Nor can Venner be said to have proven anything through his self-annihilation. On these accounts, then, wisdom must doubt that the suicide had any solid moral or intellectual motivation and it must judge that the act’s incoherence matches the incoherence that Venner himself saw in the modern condition.

The chapter of The Shock that follows “Hidden Heroic Europe” bears the title “In the Face of Death.” This chapter concerns itself with the “tradition of voluntary death.” Returning to the theme of Stauffenberg’s death, Venner characterizes it anew as, “not strictly speaking, a suicide, but… certainly not far removed.” Facing death, Stauffenberg “had finally become the hero he had dreamt of becoming,” and he thereby “in a self-sacrificial manner” achieved his goal “to leave a mark on history.” Stauffenberg thus resembles the heroes of the Trojan War, to whom the oracles of the gods had vouchsafed knowledge of imminent death in battle, but who battled with courage despite that knowledge in order to achieve quasi-immortality in the proper heroic cults that would survive them. Strictly speaking, however, such deaths are not suicides. Venner writes that Catholicism “has condemned suicide since Saint Augustine, who was simply repeating metaphysical arguments developed by Plato”; on the other hand, “the stoic tradition of Rome held [suicide] in high regard, and has offered a number of exceptionally heroic examples.” He gives the Roman instances of Lucretia, Cato, and the Prefect Publius Spendius under the reign of Caracalla, but he omits Seneca and Petronius. Among the Greeks he mentions Empedocles, who legendarily threw himself into the crater of Aetna. Among the moderns, Venner feels the attraction of Yukio Mishima, in whose Bushido discipline he undoubtedly saw another reflection of himself. He feels likewise the attraction of Henry de Montherlant, a writer, who, in 1972, “threatened with the prospect of becoming blind and refusing to endure such a fate… took a handgun and [he] shot himself in the head.” While reasonable people will understand, although not necessarily validate, Montherlant’s lethal choice, Mishima’s elaborate public suicide, like Venner’s, has about it the taint of a sordid exhibitionism. Perhaps it was coherent in a Japanese context, but Venner was French, not Japanese.

The chapter of The Shock that follows “Hidden Heroic Europe” bears the title “In the Face of Death.” This chapter concerns itself with the “tradition of voluntary death.” Returning to the theme of Stauffenberg’s death, Venner characterizes it anew as, “not strictly speaking, a suicide, but… certainly not far removed.” Facing death, Stauffenberg “had finally become the hero he had dreamt of becoming,” and he thereby “in a self-sacrificial manner” achieved his goal “to leave a mark on history.” Stauffenberg thus resembles the heroes of the Trojan War, to whom the oracles of the gods had vouchsafed knowledge of imminent death in battle, but who battled with courage despite that knowledge in order to achieve quasi-immortality in the proper heroic cults that would survive them. Strictly speaking, however, such deaths are not suicides. Venner writes that Catholicism “has condemned suicide since Saint Augustine, who was simply repeating metaphysical arguments developed by Plato”; on the other hand, “the stoic tradition of Rome held [suicide] in high regard, and has offered a number of exceptionally heroic examples.” He gives the Roman instances of Lucretia, Cato, and the Prefect Publius Spendius under the reign of Caracalla, but he omits Seneca and Petronius. Among the Greeks he mentions Empedocles, who legendarily threw himself into the crater of Aetna. Among the moderns, Venner feels the attraction of Yukio Mishima, in whose Bushido discipline he undoubtedly saw another reflection of himself. He feels likewise the attraction of Henry de Montherlant, a writer, who, in 1972, “threatened with the prospect of becoming blind and refusing to endure such a fate… took a handgun and [he] shot himself in the head.” While reasonable people will understand, although not necessarily validate, Montherlant’s lethal choice, Mishima’s elaborate public suicide, like Venner’s, has about it the taint of a sordid exhibitionism. Perhaps it was coherent in a Japanese context, but Venner was French, not Japanese.

The themes of human sacrifice and human self-sacrifice belong, first of all, to prehistoric and antique religion. When human sacrifice began to constitute a moral embarrassment to civilized people, suicidal self-immolation or self-banishment could partly substitute for its removal by partly duplicating its function. The action of Oedipus Rex would hardly be tragic if Sophocles had made his Thebans to solve their problem modo grosso by forming a mob and lynching their suddenly troublesome monarch. Rather in Sophocles’ drama, Oedipus is made decorously to self-blind and self-exile for the sake of his city, Thebes, which is thereby purified. (Meanwhile Queen Jocasta kills herself offstage.) In the sequel, Oedipus at Colonnus, with Athens and Thebes fighting over the blind vagrant who has now become a living oracle, and thus a coveted asset, the self-exile undergoes apotheosis in a flash of light that removes him from the mortal realm. In discussing a similar apotheosis said to have befallen Romulus at the end of his kingship, Livy remarks that that is the story, but he immediately adds that not a few rationalists suggest that the Senate, growing annoyed at the king’s increasing despotism, formed a mob and did away with him in a kind of Dionysiac sparagmos. The probable sacrifice of Romulus establishes the real beginning of the Roman Republic, just as the highly sacrificial murder of Julius Caesar in the foyer of the Senate establishes the real beginning of the Roman Empire. Romans of the Imperial centuries disdained human sacrifice in principle, but they ruthlessly executed criminals and dissidents in public and enjoyed blood-sport as entertainment. Venner seems unaware of this aspect of antique society, or if he were aware of it, he would have deliberately elided it.

It will be useful at this point to invoke another countryman-contemporary of Venner, the late René Girard (1923 – 2015), who left France for the United States in the 1947, became a naturalized citizen, and worked his way up to a professorship at Stanford that he held for four decades. Modern people might have learned from the work of Girard, if they had ever bothered to read him, that, however great Classical Antiquity was, especially in the form of the Roman Empire, it had its social organizing principle in sacrifice, including blatant and, latterly, surreptitious human sacrifice. In Girard’s interpretation, massively argued in a fifty-year archive of books, articles, and interviews, Christianity takes a unique place among religions in that it rejects and anathematizes sacrifice. Christianity anathematizes suicide because, quite as Venner himself argues, the circles of suicide and sacrifice blend together in the diagram and become confused. Even respecting fatal martyrdom, Christian authorities, especially in the Greek-speaking East, discouraged it. The martyrs of the arenas in Rome and elsewhere were sacrificial victims, but not of Christianity; rather, of the Imperial state. The Christian Roman Empire committed in its turn many moral enormities, beginning under the reign of Theodosius I, with a ramping-up under Justinian, two nominally Christian emperors who behaved more like Caliphs than like Christians. Under Christianity, however, gladiatorial exhibitions came under a ban – a moral advance, certainly, for humanity – and the family, which Venner extols, and which had fallen into decadence in Paganism’s late phase, enjoyed reinvigoration. Under the Christian dispensation, Europe would see the gradual disappearance of slavery, here and there by simple abandonment of the institution, but elsewhere by legal abolition. The medieval peasants were not slaves although they are often made to appear so in fatuous modern representations of the era.

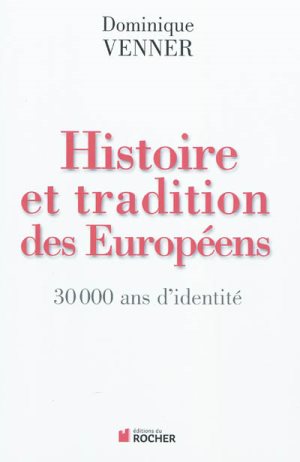

When Venner condemns Christianity, his condemnation justly applies to Theodosius, Justinian, and those like them who have interpreted the Gospel the way that Muslims interpret the Koran and whose internal crusades against heretics and Pagans anticipated jihad. Venner’s condemnation also justly applies to those medieval clerics against whom, for their zealous attempts to extirpate every last vestige of Paganism, he lavishes no little ire in his Histoire et tradition des Européens (2002), the grand summation of his thinking. Venner writes in the chapter concerning “Nihilisme et saccage de la Nature,” of a rupture of man from nature that occurred in the early medieval centuries as Christianity replaced and then attempted to suppress the immemorial cults of Pagan localism in Europe. In Venner’s words, “Having adopted [the Biblical] God… having made of him a universal deity, transplanted out of his native habitat, nascent Christianity took over his roster of anathemas.” Venner quotes Gregory of Tours as “thundering against the Franks” because of their insistence on maintaining their forest altars. For some among the clerisy, the nature-spirits had become hellish imps deserving only of exorcism. At the same time, Venner sees what he calls “the resistance [résistance] of the medieval forest divinities,” that is to say, the stubbornness of the people concerning their cults. Seeing in the High-Medieval iconography of the cathedrals a resumption of Neolithic animal-imagery and identifying that imagery with the nature-spirits of the cults, Venner remarks that, “Beyond the Eleventh Century of our era, animals again find themselves frequently represented in religious statuary.”

When Venner condemns Christianity, his condemnation justly applies to Theodosius, Justinian, and those like them who have interpreted the Gospel the way that Muslims interpret the Koran and whose internal crusades against heretics and Pagans anticipated jihad. Venner’s condemnation also justly applies to those medieval clerics against whom, for their zealous attempts to extirpate every last vestige of Paganism, he lavishes no little ire in his Histoire et tradition des Européens (2002), the grand summation of his thinking. Venner writes in the chapter concerning “Nihilisme et saccage de la Nature,” of a rupture of man from nature that occurred in the early medieval centuries as Christianity replaced and then attempted to suppress the immemorial cults of Pagan localism in Europe. In Venner’s words, “Having adopted [the Biblical] God… having made of him a universal deity, transplanted out of his native habitat, nascent Christianity took over his roster of anathemas.” Venner quotes Gregory of Tours as “thundering against the Franks” because of their insistence on maintaining their forest altars. For some among the clerisy, the nature-spirits had become hellish imps deserving only of exorcism. At the same time, Venner sees what he calls “the resistance [résistance] of the medieval forest divinities,” that is to say, the stubbornness of the people concerning their cults. Seeing in the High-Medieval iconography of the cathedrals a resumption of Neolithic animal-imagery and identifying that imagery with the nature-spirits of the cults, Venner remarks that, “Beyond the Eleventh Century of our era, animals again find themselves frequently represented in religious statuary.”

Venner’s word-choice of résistance endows itself with an abundance of connotations relevant to his own case. In endorsing that résistance retroactively Venner declares himself a Nineteenth Century Romantic in the line of Alfred de Vigny, Alphonse de Lamartine, and Victor Hugo. He would also align himself with the English and German Romantics of the same period. The difference between Venner and the Romantics is that while they cherished in the Middle-Ages the same vestiges of Paganism as did Venner, they never, as Venner does, rejected the Christian content of that historical period. They could see the Western Tradition as having nurtured a startling synthesis. When the Romantics defended old customs and conventions, they were defending the synthesis of them with the Gospel against a new materialistic and positivistic order that was vehemently inimical to any spiritual value or perception, whether Christian or Pagan. Almost everywhere in his work, Venner remains blind to that aspect of Christianity which not only could, but did, find a way to meld itself with what was redeemable in Paganism. Whereas contemporary environmentalism, for example, suffers distortion under ideological influence, it nevertheless reflects an intuition about nature that can trace itself back through Romantic sensibility to the ethos of Francis of Assisi’s canticle “Brother Sun and Sister Moon” and behind that to a combination of the Pagan sense of genius loci and the philosophical pantheism of Late Antiquity. Let it only be noted that neither St. Francis nor the philosophical pantheists ever sacrificed anything to les divinités sylvestres. Venner has a thing about Christianity, undoubtedly, which results in an unfortunate tendency in his discourse.

II. The limitations in Venner’s thought once established, it becomes possible to set forth in parallel an apology for his philosophical contribution. Venner’s active participation in an organized and at times armed resistance to the pernicious agenda of the liberal-totalitarian regime constitutes no small part of his achievement. Most of Traditionalism is and has been intellectual. Even where Traditionalism’s intellect is active and aggressive it never exactly puts its life on the line. Venner put his life on the line (he could have been executed), something to be respected, and a model that some committed people might one day, and in the not-too-distant future, find themselves called on to imitate. This is especially the case in Europe, where liberalism has long since reached its nakedly totalitarian phase and is allying itself with Islam. In this way the figure among the Twentieth Century’s first-generation Traditionalists whom Venner most closely resembles is Julius Evola. Venner’s masterpiece, the Histoire, is a contemporary counterpart of Evola’s earlier Revolt against the Modern World (1969). Venner’s Shock resembles Evola’s Path of Cinnabar (1963) in that, like The Path, it is a late-in-life autobiographical summing-up and commentary on the author’s previous work. Venner directs some criticism at Evola, whom he lumps together with René Guénon. “The anti-materialism of this school is stimulating,” he writes in the Histoire; but because anti-materialism alone is “incapable of going beyond an often legitimate critique [to] propose an alternative way of life,” as he adds, it tends to retreat into “eschatological waiting for catastrophe.” Unlike Guénon and Evola, Venner believed in no singular primordial tradition, but in plural traditions linked to particular peoples.

Venner established himself early and impressively as an historian and essayist, founding and editing journals, and producing books prolifically. Among his early book publications, one finds the title Baltikum: dans le Reich de la défaite, le combat des corps-francs, 1918-1923 (1974), a study of the largely German independent armies that fought in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania after the Allied victory in 1918 to prevent the Red Army from re-annexing those newly proclaimed sovereignties to Russia, now the USSR. The topic would have exerted its attraction on Venner because of his experience as a member of a later corps-franc, the outlawed OAS. Venner grasps that among the innumerable catastrophes of the First World War, and certainly not the least among them, was the German defeat. That defeat opened up an abyss of disorder that the forces of revolution, not least the USSR, immediately exploited both in the former Reich and in adjacent territories. Allied vengefulness exacerbated the problem. Venner represents the corps-francs as arising spontaneously in an attempt to preserve order against the tide of chaos. That the corps-francs themselves degenerated into chaos makes of them a tragic indicator of the times. In a follow-up, Histoire d’un fascisme allemand: les corps-francs du Baltikum et la révolution (1996), Venner traced the political consequences of the Baltic debacle. Venner also devoted a book-length study to the Civil War in Russia, Les Blancs et les Rouges: histoire de la guerre civile russe, 1917-1921 (1997), and another, Gettysburg (1994), to that decisive battle of the American Civil War.

Unsurprisingly, considering Venner’s military experience, weaponry fascinated him. Many of Venner’s books – a large percentage of them, in fact – are dedicated to arms: To muskets antique and modern, pistols antique and modern, the Mauser nine-millimeter pistol, which receives a whole book, and cutting blades and stabling blades. Like José Ortega and Siegfried Sassoon, Venner wrote about hunting, of which sport he was an aficionado. Insofar as the name Venner means anything in the Anglophone world, however, that meaning is related to his analysis of the liberal-totalitarian regime and his articulation of a counter-modern identitarian tradition able to be embraced by all of the European peoples including those in the Slavic East. The major locus of these two discursive activities is the Histoire. In The Shock, which Venner wrote at the request of Arktos Press to introduce himself to English-speaking audiences, he describes the Histoire as “a book about history and tradition” provoked by its author’s sense of “the degradation and blame imposed on Europe in the second half of the twentieth century.” Venner wishes to be as clear as possible concerning what he means by that term tradition which people tend to associate with a superseded and irretrievable past. On the contrary, “it is not the past, [but rather] it is that which does not pass away.” Tradition “comes to us from that which is most distant, but always present,” forming an “interior compass, the benchmark of all the norms that suit us and that have survived all that has tried to change us.”

Unsurprisingly, considering Venner’s military experience, weaponry fascinated him. Many of Venner’s books – a large percentage of them, in fact – are dedicated to arms: To muskets antique and modern, pistols antique and modern, the Mauser nine-millimeter pistol, which receives a whole book, and cutting blades and stabling blades. Like José Ortega and Siegfried Sassoon, Venner wrote about hunting, of which sport he was an aficionado. Insofar as the name Venner means anything in the Anglophone world, however, that meaning is related to his analysis of the liberal-totalitarian regime and his articulation of a counter-modern identitarian tradition able to be embraced by all of the European peoples including those in the Slavic East. The major locus of these two discursive activities is the Histoire. In The Shock, which Venner wrote at the request of Arktos Press to introduce himself to English-speaking audiences, he describes the Histoire as “a book about history and tradition” provoked by its author’s sense of “the degradation and blame imposed on Europe in the second half of the twentieth century.” Venner wishes to be as clear as possible concerning what he means by that term tradition which people tend to associate with a superseded and irretrievable past. On the contrary, “it is not the past, [but rather] it is that which does not pass away.” Tradition “comes to us from that which is most distant, but always present,” forming an “interior compass, the benchmark of all the norms that suit us and that have survived all that has tried to change us.”

Venner admits to LeComte in The Shock that his pushing-back of the lower limit of the European cultural tradition is a gesture of deliberate audacity, but he makes a case for that audacity. In the Histoire itself he writes how, “For Europeans, as for other peoples, the authentic tradition can be none other than their own”; and he makes the important gesture, crucial to the argumentative structure of the book, of opposing Tradition to nihilism: “It is [tradition] that opposes nihilism by a return to the specific sources of the ancestral soul (âme ancestrale).” Moreover, “The contrary of the tradition is not modernity, a confused and limited concept, but nihilism.” Modernity can make itself compatible with tradition, but nothing is compatible with nihilism, which is both thoughtless, its endless torrent of polysyllables notwithstanding, and voracious. Tradition regards the human being as trifunctional: It places the functions in a hierarchy, with reason, in communion with the divine, at the top; courage in the middle, and the pair, desire and appetite, at the bottom. Like the divinity with which it communes, reason brings the lower functions into proper order by injunction. Nihilism is the triumph of desire and appetite over the injunctions of reason and courage. This triumph did not happen in a day. In an early chapter of the Histoire, Venner claims to detect the first stirrings of revolt in the Summa of Thomas Aquinas, which, in his view, framed as dogma the subordination of reason to unthinking faith. Venner characteristically prefers Pagan over Christian philosophy.

Venner finds a later stage of the nihilistic revolt in the philosophical method of René Descartes. Whereas, on the one hand, for Aquinas “reason [had] associated itself with faith so as to clarify rectitude,” as Venner writes; for Descartes, on the other hand, the only purpose of reason was “to satisfy itself,” as in the declaration, “je pense, donc je suis.” The human person becomes a hermetic subject, regarding itself in a gesture of hubris as “central to the universe.” Egocentric desire, subordinating reason, now seeks to satisfy itself through pure calculation; its main task is to manipulate a radically de-divinized external world that it sees only as a magazine of resources making itself available to a selfish will. In Venner’s history of nihilism, Thomas Hobbes represents yet another stage of degeneration. According to Venner’s reading, nature horrified Hobbes, for whom, rather than an external model of order as it had been for the Pagans, it was a reprehensible chaos requiring suppression. Venner again sees Adam Smith and Karl Marx as alike starting from the Cartesian standpoint of an imperious, but vitally evacuated, ego. He points out that both men aimed at arrangements which were supposed to satisfy appetite optimally if not maximally, with reason demoted to a mere means. Whether for Smith or Marx, in Venner’s reading, man is an insipid homo oeconomicus. That the brutal Marxist variety of communism failed spectacularly consoles Venner not at all because, as he sees things, the globalizing of American-style consumer-society amounts to a type of “market communism,” no less inhuman in its consequences than Leninism-Stalinism because it reduces everything to material and logistical processes.

It is an achievement to describe something meticulously and accurately. Venner himself admires meticulous and accurate description. He cites from the dystopian tradition in Twentieth Century literature, especially from Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, but also from underappreciated writer-thinkers like Flora Montcorbier, from whom he borrows the phrase “market communism.” Venner’s description of the cultural nullity, the malicious jejuneness, and the righteous moral intolerance of the relentlessly self-exporting postmodern American-global regime is one of the highlights of the Histoire. Coming near the end of the book, in the chapter (10) on “Nihilisme et saccage de la nature,” it also provides a grand rhetorical climax. Venner appropriates a widely current trope from contemporary popular culture: The Zombie – that paradoxical incarnation of nullity – that voracious cipher of the global consumerist dystopia – who submits to the perverse “religion of humanity.” It is the Mephistophelean cleverness of nihilism to disguise itself under the trappings of a noble creed. In the aftermath of World War Two, America wanted to make the market “the main determiner of economic rationality and change”; but the Communists wanted “to pool the wealth of humanity and put it under rational management.” Both systems aimed at the creation of a new type of man, whose apparition required the obliteration of the old type of man. The synthesis of the two means directing themselves at the common goal was “market communism, another name for globalism,” which is in turn but another name for nihilism disguising itself as the religion of humanity. Venner uses his formulation, the religion of humanity, of course, with the highest degree of irony.

It is an achievement to describe something meticulously and accurately. Venner himself admires meticulous and accurate description. He cites from the dystopian tradition in Twentieth Century literature, especially from Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, but also from underappreciated writer-thinkers like Flora Montcorbier, from whom he borrows the phrase “market communism.” Venner’s description of the cultural nullity, the malicious jejuneness, and the righteous moral intolerance of the relentlessly self-exporting postmodern American-global regime is one of the highlights of the Histoire. Coming near the end of the book, in the chapter (10) on “Nihilisme et saccage de la nature,” it also provides a grand rhetorical climax. Venner appropriates a widely current trope from contemporary popular culture: The Zombie – that paradoxical incarnation of nullity – that voracious cipher of the global consumerist dystopia – who submits to the perverse “religion of humanity.” It is the Mephistophelean cleverness of nihilism to disguise itself under the trappings of a noble creed. In the aftermath of World War Two, America wanted to make the market “the main determiner of economic rationality and change”; but the Communists wanted “to pool the wealth of humanity and put it under rational management.” Both systems aimed at the creation of a new type of man, whose apparition required the obliteration of the old type of man. The synthesis of the two means directing themselves at the common goal was “market communism, another name for globalism,” which is in turn but another name for nihilism disguising itself as the religion of humanity. Venner uses his formulation, the religion of humanity, of course, with the highest degree of irony.

Venner writes: “In order to change the world, [the system] must change man; it must manufacture the Homo Economicus of the future, the zombie, the man born of nihilism, emptied of content, and possessed by the spirit of the market and universal humanity.” Not everyone willingly accepts zombification. Pockets of dissent rally around the vestiges of tradition to mount resistance to the agenda of dehumanization. What then? “As the design is grandiose, one must not skimp in fashioning the means to break [such resistance]… The world is full of potential recalcitrants who must be put down or re-educated.” While agents of the thought police harass well-known individual dissenters, the managerial class applies general reconstructive pressure on the native populace through the imposition of migrants on existing communities. In Venner’s description, “The permanent installation of immigrant communities accelerates the proletarianization of immigrants themselves, but also of the indigenous working class, the ‘little whites,’” and thus also “naked proletarians” who are “potential zombies.” The managerial class also uses immigration to stoke the guilt that constitutes the evil heart of the religion of humanity. Venner argues that “victimology [he means victim status] has become the litmus… of legitimacy in a society that is hardly itself legitimate.” Immigrants endear themselves to the regime because it can claim them as the victims of the autochthons; the persecution of the autochthons even extends backwards temporally, as “the society sets itself up as a tribunal of a past it has criminalized.”

The tradition that the new society of secular saints and morality policemen would annihilate, and on knowledge of which depends the identitarian continuity of Western Civilization, begins, as Venner’s title boldly suggests, thirty thousand years in the past, in the cave paintings and related artifacts that reveal themselves in a swatch of Europe stretching from Spain and France in the west to the Ural Mountains in the east. “By its ancientness and homogeneity in painting and carvings of every sort, this religiously inspired, animal dominated art is specific to Europe and to her alone.” Venner identifies this art with the remotest ancestors of the Indo-Europeans. Impressively, this school or style, associated with images of the hunt, would sustain itself unbroken for nearly twenty thousand years – or from 32,000 years ago until 12,000 years ago, when agriculture and animal husbandry began at last to supplant the hunt as European humanity’s chief activities. It is important to Venner’s argument that while Paleolithic men undertook the hunt, they did so under the aegis of their goddesses. As Venner writes, “the huntress divinities… survived, leaving traces as late as the historical periods.” Think of the Greek goddess Artemis. Quoting Ernst Jünger, Venner emphasizes the spirit of freedom (liberté) that animates the cave paintings no matter their place in the chronology.

The prominence of the female sex in the European tradition indeed belongs at the heart of Venner’s exposition. That public and effective presence of women strongly differentiates the European tradition from other traditions, in Venner’s view. In the case of the Homeric poems, for example, it is women who have set the train of events in motion – first the goddesses, by recruiting Paris to judge them, and then Helen, whose beauty drives Paris to flout the hospitality of King Menelaus and elope with his host’s wife. The Greek war against Troy is the result. Homer never settles blame on Helen and neither does Venner. Like Penelope, her counterpart in the Odyssey, Helen adapts to circumstance without ever compromising her dignity. Of Penelope, Venner remarks how in Homer’s poem readers “see her sweet and attentive with her son,” but also “disquieted and languishing over the thought that her husband might have vanished forever.” Penelope for Venner is archetypal: “Her conduct is beyond suspicion and dignified, but she is woman, subject to anxiety, suffering ever and again from the secrets of her nature.” On the other hand, she has upheld her home for twenty years and schemes actively against the trespassing suitors. Venner finds these traits again and again in European literature’s treatment of women, whether ancient or medieval. Homer’s hero Odysseus not incidentally is a hunter, who enjoys the aide and counsel of a goddess, Athene.

Venner sees Agamemnon’s punitive expedition against Troy as feudal: “The Greeks who set siege to Troy are not an army in the modern sense, but an assembly of independent bands, each following a renowned captain on a raid of reprisal in hope of booty.” Venner sees feudalism (féodalité) as characteristic of spontaneous self-organization among the European peoples, feudalism reflecting the European archetype of trifunctionality, a notion that he borrows from Georges Dumézil. The feudal principal is above all a local principle, under which a people attached to its soil practices arms to defend the land and recognizes the merit of the most skilled at arms. The people are free – and they meet in free assemblies the model of which already appears in the warrior councils of the Iliad and the Odyssey, as well as in the Roman Senate, the Scandinavian Thing, and the Parliaments of medieval French and English traditions. The best-at-arms may enjoy elevation to dukedom or nominal kingship, but the principality remains constitutional even where there is no written document. Venner interprets Bronze-Age archaeology in particular, from Scandinavia to the Aegean, as testifying to “a new and audacious culture” that sets the pattern for three millennia of continuous development and that articulates itself verbally in epic and saga. He enumerates the basic elements of that culture as “a new solar religion… tragic heroism in the face of Destiny, suffering and death, individuality and the verticality of the hero as opposed to indistinct horizontality of the multitude”; also “valiance, the essential masculine virtue” along with respect and admiration for femininity.

Venner sees Agamemnon’s punitive expedition against Troy as feudal: “The Greeks who set siege to Troy are not an army in the modern sense, but an assembly of independent bands, each following a renowned captain on a raid of reprisal in hope of booty.” Venner sees feudalism (féodalité) as characteristic of spontaneous self-organization among the European peoples, feudalism reflecting the European archetype of trifunctionality, a notion that he borrows from Georges Dumézil. The feudal principal is above all a local principle, under which a people attached to its soil practices arms to defend the land and recognizes the merit of the most skilled at arms. The people are free – and they meet in free assemblies the model of which already appears in the warrior councils of the Iliad and the Odyssey, as well as in the Roman Senate, the Scandinavian Thing, and the Parliaments of medieval French and English traditions. The best-at-arms may enjoy elevation to dukedom or nominal kingship, but the principality remains constitutional even where there is no written document. Venner interprets Bronze-Age archaeology in particular, from Scandinavia to the Aegean, as testifying to “a new and audacious culture” that sets the pattern for three millennia of continuous development and that articulates itself verbally in epic and saga. He enumerates the basic elements of that culture as “a new solar religion… tragic heroism in the face of Destiny, suffering and death, individuality and the verticality of the hero as opposed to indistinct horizontality of the multitude”; also “valiance, the essential masculine virtue” along with respect and admiration for femininity.

With valiance comes chivalry, already present in Odysseus’ behavior toward Nausicaä and Penelope, but coming into flower, of course, in the medieval centuries. Aware, no doubt, of Henri Pirenne’s revised model of Late Romanitas — in which the Roman Empire suffers no dramatic fall and disappearance but rather morphs into its Gothic successor-states, which then base themselves on the Imperium and seek to preserve it — Venner also rejects the notion of a “brutal rupture” at the end of the Fifth century and a subsequent precipitous descent into cultural darkness. “The truth is that the Germans conquered neither the Roman Empire nor Roman Gaul”; quite to the contrary, “the political power gradually exercised in Gaul by [the Goths] issued not in conquest but in their romanization.” Even the cultural variety of the Gothic principalities reflects something of the Roman Empire. Venner emphasizes the cultural disinterest of Roman imperial policy: “The Empire largely respected the laws and customs of each people, at least until the adoption of Christianity.” Once again, however, Venner regards the Christianity of the Medieval Period as a synthesis, often even a bit more heathen than Christian. He writes, for example, of Clovis that, “as did Constantine in his time, Clovis was baptized, an eminently political act which ensured the support of the episcopate, that is to say, the Gallo-Roman nobility.” Venner would make of the Meroving war-leader’s famous victory over the jihad at Tours in 732, which kept Islam out of Western Europe, something like a Late-Roman victory.

Venner characterizes the “Golden Age” of Medieval Europe – around the Millennium and after the breakup of Charlemagne’s kingdom – under the formula of “une révolution castrale,” a more or less untranslatable phrase denoting the rise of small principalities based on the chateau or castle-mansion of the local duke or prince or king. The ethos of les châteaux et les châtellenies, in Venner’s view, reflects the variety-in-unity of the Medieval European tradition. “With their Celtic spaciousness, their dungeons of Norman style, their Roman courtines and towers, the chateaux are representative of the diverse historical heritages which produce the medieval [institution of] nobility.” Each castle-mansion serves as an administrative center for a vassalage and peonage that the aristocracy can know personally; each is a seat of high justice, and each is a foyer, as Venner puts it, of culture. The chateau constitutes a state, but it is a state “decentralized, personalized, living, and rooted.” Venner has something in common with Aristotle, who argued that once the polis exceeded fifty thousand citizens it would become errant and unlivable. Venner likewise has something with E. F. Schumacher, in whose famous phrase, “small is beautiful.”

The révolution castrale, absorbing so much of the pre-Christian spirit, gave Western Europe, among other things, those remarkable narratives, the Arthurian romances and Grail-Quests, which Venner regards as equaling the great epic poems of Classical Antiquity. Venner devotes an entire chapter (8) to la matière de Bretagne, which he explicates as codifications of the chivalric code. He accomplishes his explication less by reference to the texts themselves than by their brilliant summation (as he sees it) in John Boorman’s 1981 film, Excalibur. Venner’s gesture is an important one. It reminds his readers that he makes no blanket rejection of contemporary artistic endeavors or of popular genres. He considers Boorman’s film a genuine revival of the Arthurian spirit and an indication therefore that Arthurian spirit has not been extinguished, but smolders yet, ready to be fanned back into life. One recalls Venner’s remark that the tradition consists of what has not died but is perennially present even when unseen. Distilling the literary Grail-Romance to its essence, Excalibur tells the story how chaos becomes order under the typically European forms. Boorman’s decision to use Richard Wagner’s music from The Ring, as Venner remarks, calls attention to the periodic revival of the forgotten lore in Western art, even in the dolorous Endarkenment of late modernity.

The révolution castrale, absorbing so much of the pre-Christian spirit, gave Western Europe, among other things, those remarkable narratives, the Arthurian romances and Grail-Quests, which Venner regards as equaling the great epic poems of Classical Antiquity. Venner devotes an entire chapter (8) to la matière de Bretagne, which he explicates as codifications of the chivalric code. He accomplishes his explication less by reference to the texts themselves than by their brilliant summation (as he sees it) in John Boorman’s 1981 film, Excalibur. Venner’s gesture is an important one. It reminds his readers that he makes no blanket rejection of contemporary artistic endeavors or of popular genres. He considers Boorman’s film a genuine revival of the Arthurian spirit and an indication therefore that Arthurian spirit has not been extinguished, but smolders yet, ready to be fanned back into life. One recalls Venner’s remark that the tradition consists of what has not died but is perennially present even when unseen. Distilling the literary Grail-Romance to its essence, Excalibur tells the story how chaos becomes order under the typically European forms. Boorman’s decision to use Richard Wagner’s music from The Ring, as Venner remarks, calls attention to the periodic revival of the forgotten lore in Western art, even in the dolorous Endarkenment of late modernity.

Whether it is Achilles or Odysseus, Arthur or Roland, Leif Eriksson or Charlemagne, the Western hero invariably bodies forth the ancestral forms. Those forms, those “lived values” of the European identity, carry within them the power, as Venner writes, to “put one on guard against nihilism.” What are the forms specifically? They have a Roman pedigree. They are “the dignitas of nobility, the virtus of the citizen, and the devotio of the leader who gives the gift of his person to his country.” Venner finds these valeurs in names to be added to his gallery of admirable men – the Russian Prime Minister Stolypine, the Emperor Franz-Joseph, and the Finnish Field Marshal who fought the Red Army to a standstill in Karelia, Gustav Mannerheim. The History and Tradition of the European Peoples belongs on the shelf with Evola’s Revolt against the Modern World (1969) and Guénon’s Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times (1945).

III. The BBC obituary for Venner (21 May 2013) begins with the following sentence: “Dominique Venner, the far-right French essayist who shot himself before the altar of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris on Tuesday, was a bitter opponent of same-sex marriage and influence of Islam in France.” The obituarist for The Daily Beast (23 May 2013), after noting its subject’s transformation from active insurrectionist to contemplative historian, writes: “Venner and the Nouvelle Droite never for a second veered from their racialized supremacism. Not only is it present in Venner’s writings but even in his final blog post, in which he cited The Camp of the Saints, a fictional screed about the obliteration of Western culture by immigrants authored by the racist ideologue (and fellow Académie Française prize winner) Jean Raspail.” For its part the New Yorker obituary (22 May 2013) attests that, in his suicide-note, Venner “singled out Muslims – he was an unapologetic Islamophobe – but… also evoked the racist, xenophobic, and anti-Semitic rhetoric of the Fascist European right between the two World Wars, which has been moderated, though not abolished, by postwar hate-speech laws.” Judith Thurman, the New Yorker obituary writer, finishes up by noting Venner’s admiration for Yukio Mishima, adding this: “It is, perhaps, apt to note in this context that Mishima’s works are rife with homoerotic imagery and sadomasochism, that he was known to frequent the gay bars of Tokyo, and that his early novel ‘Confessions of a Mask’ tells the story of an anguished, alienated teen-age boy, coming of age in repressed postwar Japan, who discovers that he is gay.” As Venner writes in the Histoire: “The thought police meanwhile never cease to hunt down Evil, that is to say, the fact of being different, being individuated, loving life, nature, the past, cultivating critical thinking and refusing to sacrifice to the universal deity.”

What would happen if the critic, momentarily adopting the spirit of the times, submitted the three sample obituaries to the Left’s much-touted deconstructive procedure? The critic would begin by noting that the regime, lacking the wordbook of objectivity, can discuss nothing except in the Manichaean dichotomies of its socialist rhetoric. Thus for the BBC writer, Venner was “far-right,” the opposite term to his own far-left conviction, which, of course, he does not need to mention, as his readers share and assume it. For the BBC writer, no opponent of homosexual marriage or Islamic immigration can be anything other than “bitter.” (Recall Barack Obama’s characterization of Southern Christians as bitter clingers.) Nor apparently is immigration an allowable term: Islam’s presence in Europe must be reduced to the rhetorically neutral term influence, as though the hundreds – or is it now thousands – of victims of Muslim sexual mayhem and murderousness in France, Germany, Norway, and Sweden had encountered nothing more than the benignity of classical oratorical persuasion. Again for the Daily Beast writer, in discussing dissentient views, there may be nothing except pejorative hyperbole. For him, to defend Europeans and European civilization, to suggest that there should be limits on immigration, or perhaps a ban, is to engage in “racial supremacism,” while the creedal super-bigotry of Islam scuffles away out of sight.

What would happen if the critic, momentarily adopting the spirit of the times, submitted the three sample obituaries to the Left’s much-touted deconstructive procedure? The critic would begin by noting that the regime, lacking the wordbook of objectivity, can discuss nothing except in the Manichaean dichotomies of its socialist rhetoric. Thus for the BBC writer, Venner was “far-right,” the opposite term to his own far-left conviction, which, of course, he does not need to mention, as his readers share and assume it. For the BBC writer, no opponent of homosexual marriage or Islamic immigration can be anything other than “bitter.” (Recall Barack Obama’s characterization of Southern Christians as bitter clingers.) Nor apparently is immigration an allowable term: Islam’s presence in Europe must be reduced to the rhetorically neutral term influence, as though the hundreds – or is it now thousands – of victims of Muslim sexual mayhem and murderousness in France, Germany, Norway, and Sweden had encountered nothing more than the benignity of classical oratorical persuasion. Again for the Daily Beast writer, in discussing dissentient views, there may be nothing except pejorative hyperbole. For him, to defend Europeans and European civilization, to suggest that there should be limits on immigration, or perhaps a ban, is to engage in “racial supremacism,” while the creedal super-bigotry of Islam scuffles away out of sight.

The New Yorker’s Thurman serves up a particularly rich effluvium of hypocritical vituperation. For hypocrisy, take her phrase to single out. Venner, like others of his ilk, tirelessly admonished a misled public that Islam is not a religion like any other, but an extraordinarily peculiar and savage doctrine that singles out everyone who is not a Muslim – and singles him out for persecution and murder. If the scapegoating formula to single out were to be employed properly, it would necessarily be applied to Islam, not to the critics thereof. Yet it is Venner, in Thurman’s diction, who qualifies as “an unapologetic Islamophobe,” that final term serving like racist or sexist to mean anyone with whom the writer disagrees. Unsurprisingly, the word racist is next up in the verbal order and sexist immediately after. Thurman would have her readers believe that “postwar hate-speech laws,” a phenomenon of the last two decades, ended Fascist rhetoric; when in fact it was Allied blood and treasure in World War Two, culminating in the revelation of the death camps, which made such rhetoric shameful – except in Islam. Thurman now executes her nastiest whopper of all by implying that Venner felt attracted to homosexuality and sadomasochism. The gesture is remarkable for its blatant self-exception from liberal principles. For the good liberal, there is nothing wrong with homosexuality – in fact, it is a positive good – whereas sadomasochism is merely a private matter. In the case of Venner, however, these two sacred things constitute a tar-bucket of moral condemnation that Thurman may apply as thickly she likes.

Consider the obituaries that ensued on the death of the philosopher Louis Althusser in 1992. Althusser was a lifetime Communist who, after murdering his wife in 1981, served a lenient prison sentence that lasted a mere three years. The New York Times obituary (24 October 1990) only mentions the murder in its fourth paragraph of thirteen. The laconic first paragraph reports the bare fact that “Louis Althusser, a French Communist philosopher who was a prominent critic of French and Soviet Communism in the 1970’s, died Monday of heart failure in a geriatric center outside Paris.” The second paragraph, equally bland, tells how “Mr. Althusser had taught for many years at the prestigious Ecole Normale Superior in Paris and was himself one of its graduates.” Althusser’s obituarist uses no terms that would equate to those used insultingly by the obituarists of Venner; there is in his prose almost no editorial language, unless the blandness itself is taken as editorial, which perhaps it is. Reviewing an English translation of Althusser’s posthumous memoir, a writer for The Los Angeles Times (13 March 1994) sought to mitigate the homicide: “Those who knew Althusser understood that whatever fit of madness induced him to strangle Helene was not brought on by the world of politics.” The reviewer then represented Althusser as an “elegant theorist… who redefined the concept of ‘ideology’ as ‘our imaginary relationship to real conditions of existence.’” As late as 2009 The New Left Review (No. 59, July-August) could refer to Althusser as “the unfortunate and scandalous protagonist of an unexpected fait divers, the murder of his wife Hélène, within the very walls of the École Normale.” Far from being bland, the sentence is suavely exculpatory.

Consider the obituaries that ensued on the death of the philosopher Louis Althusser in 1992. Althusser was a lifetime Communist who, after murdering his wife in 1981, served a lenient prison sentence that lasted a mere three years. The New York Times obituary (24 October 1990) only mentions the murder in its fourth paragraph of thirteen. The laconic first paragraph reports the bare fact that “Louis Althusser, a French Communist philosopher who was a prominent critic of French and Soviet Communism in the 1970’s, died Monday of heart failure in a geriatric center outside Paris.” The second paragraph, equally bland, tells how “Mr. Althusser had taught for many years at the prestigious Ecole Normale Superior in Paris and was himself one of its graduates.” Althusser’s obituarist uses no terms that would equate to those used insultingly by the obituarists of Venner; there is in his prose almost no editorial language, unless the blandness itself is taken as editorial, which perhaps it is. Reviewing an English translation of Althusser’s posthumous memoir, a writer for The Los Angeles Times (13 March 1994) sought to mitigate the homicide: “Those who knew Althusser understood that whatever fit of madness induced him to strangle Helene was not brought on by the world of politics.” The reviewer then represented Althusser as an “elegant theorist… who redefined the concept of ‘ideology’ as ‘our imaginary relationship to real conditions of existence.’” As late as 2009 The New Left Review (No. 59, July-August) could refer to Althusser as “the unfortunate and scandalous protagonist of an unexpected fait divers, the murder of his wife Hélène, within the very walls of the École Normale.” Far from being bland, the sentence is suavely exculpatory.

A current darling of the Parisian Left, Bernard Stiegler, often described by his apologists as the successor both of Martin Heidegger and Jacques Derrida, spent his twenties as a Leftwing extremist whose gang robbed banks at gunpoint. Stiegler served a prison term for his crimes from 1978 to 1983, three years longer than Venner’s incarceration. Try to find any details of Stiegler’s crimes on the Web. Vigilant parties have scrubbed the references. The Wikipedia tells only that Stiegler served time for armed robbery. One can, however, access Stiegler’s discussion of the crime of Patricia and Emmanuel Cartier entitled The Disaffected Individual in the Process of Psychic and Collective Disindividuation, which figures as the third chapter of his book Les sociétés incontrôlables d’individus désaffectés (2006). In 2005, the Cartiers, facing mounting debts, decided to kill their four children and then commit suicide. They chose for the method of homicide insulin injection. The couple managed to kill only one child, a girl, Alicia. The suicides failed. A criminal court sentenced the killers to ten or fifteen years behind bars, depending on their behavior. Stiegler poses a rhetorical question, “Does this mean that these parents no longer loved their children,” to which he answers, “Nothing is less sure.” The phrase does not complete the sentence, which carries on for something like seventy words. The upshot is: Society made them do it so that society is just as culpable as they. In a subsequent paragraph, Stiegler claims that “the Cartiers… are as much victims as perpetrators.” Stiegler’s words are, of course, fatuous, but they are also a hoary cliché. Part of the scandal of Stiegler, as of other contemporary academician-writers, is his and their purveyance of ideas that were already hackneyed in 1848 as though they were brilliant new insights. But it takes two to tango. The university-trained readership that consumes postmodern prose is equally culpable with the producers of it.

A current darling of the Parisian Left, Bernard Stiegler, often described by his apologists as the successor both of Martin Heidegger and Jacques Derrida, spent his twenties as a Leftwing extremist whose gang robbed banks at gunpoint. Stiegler served a prison term for his crimes from 1978 to 1983, three years longer than Venner’s incarceration. Try to find any details of Stiegler’s crimes on the Web. Vigilant parties have scrubbed the references. The Wikipedia tells only that Stiegler served time for armed robbery. One can, however, access Stiegler’s discussion of the crime of Patricia and Emmanuel Cartier entitled The Disaffected Individual in the Process of Psychic and Collective Disindividuation, which figures as the third chapter of his book Les sociétés incontrôlables d’individus désaffectés (2006). In 2005, the Cartiers, facing mounting debts, decided to kill their four children and then commit suicide. They chose for the method of homicide insulin injection. The couple managed to kill only one child, a girl, Alicia. The suicides failed. A criminal court sentenced the killers to ten or fifteen years behind bars, depending on their behavior. Stiegler poses a rhetorical question, “Does this mean that these parents no longer loved their children,” to which he answers, “Nothing is less sure.” The phrase does not complete the sentence, which carries on for something like seventy words. The upshot is: Society made them do it so that society is just as culpable as they. In a subsequent paragraph, Stiegler claims that “the Cartiers… are as much victims as perpetrators.” Stiegler’s words are, of course, fatuous, but they are also a hoary cliché. Part of the scandal of Stiegler, as of other contemporary academician-writers, is his and their purveyance of ideas that were already hackneyed in 1848 as though they were brilliant new insights. But it takes two to tango. The university-trained readership that consumes postmodern prose is equally culpable with the producers of it.

In The Shock of History, LeComte asks Venner why philosophers and intellectuals “become rabid defenders of lying, chimeric, and backwards systems.” Venner responds that the tendency arises from peculiarities of the European mentality, which gravitates to ever higher levels of abstraction. The abstractions acquire the rigidity of absolutes, for which “in heated collective and historical situations, men have killed and died.” More generally, the tendency arises from human nature. Beyond the physical necessities, people require meaning, which they can only find in the available symbols. The reigning modernity, long in the making, has censoriously diminished the repertory of symbols and has thereby created a crisis of meaning, among the results of which are the ugliness of the public square and the suicidal incoherency of policy, as for example in the domain of immigration. Where an impoverishment of meaning prevails, hysteria and extremism will constitute natural responses. Venner makes an historical comparison: “While the European everyman of the thirteenth century, lord or shepherd, was satisfied with a rudimentary belief in a tutelary God, the clergy’s very existence was driven by theological reflection. The same is true of the secular theologians we have today in the form of political scholars.”

According to Venner, “the intellectual is imbued to his core by the certainty that concepts are the only true facts, and that he is their enlightened interpreter, while the commoner, as in Plato’s allegory of the cave, can only discern the half-deformed shadows they cast.” The observation puts Venner in much good company. He comes parallel, for example, with Eric Voegelin’s notion of ideology as a second reality, or again with Voegelin’s contention that the modern political scene is essentially Gnostic. When Venner ascribes to the contemporary intellectual class its being intoxicated by rigid abstraction, he might as well be invoking Gnosticism. Cognoscenti of Voegelin might protest that, contrary to Venner, Voegelin discovers in Christianity an increase in the differentiation of symbols over Paganism hence also a clarification of the human predicament. Voegelin’s students would for this reason prefer his diagnosis of modernity to Venner’s because of Venner’s failure to grasp the subtleties of Christian revelation. Voegelin might be closer to Venner, however, than his partisans would think. In the fourth volume of Order and History – The Ecumenic Age (1965) – Voegelin makes a statement that a good many of his readers fail to remark. The context is Voegelin’s history of Christian symbolism from Paul to the Council of Nicaea; what impresses and pleases Voegelin in these earliest centuries of the faith, is the plasticity and plurality of its symbolism and the closeness of that symbolism to the experience of transcendence. Voegelin’s phrase for describing the phenomenon is “the openness of the theophanic field.”

Voegelin goes on to say that, “The openness of the theophanic field, though it came under pressure when the Church felt it necessary to distinguish its ‘monotheism’ from the ‘polytheism’ of the pagans, could be substantially preserved for almost three centuries.” Voegelin admires Origen, anathematized by the later clergy, for the poetic fluidity of his symbols, some of which, like the symbol of fire, show conscious continuity with the origins of philosophy, as in Heraclitus, with his fire and lightning. “Up to Nicaea (325),” Voegelin writes, “when the Athanasian victory put an end to this generous openness, Christianity was substantially ditheistic.” Elsewhere, Voegelin writes apologetically about Late-Pagan Summodeism, which approximates Christianity so closely in his view that only the doctrine-obsessed clerical mind at its most rigid could invidiously distinguish one from the other. In comparison with Venner, Voegelin must appear the more generous soul because Voegelin’s embrace reaches farther than Venner’s, finding commonality where Venner finds irreconcilable enmity. However, Voegelin’s approval of Early Christianity implies his criticism of Post-Nicene Christianity, which is not so different from Venner’s when he deplores the Old-Testament zeal of the Alexandrian bishops or the medieval heresy-hunters.

Just as Venner exhibits affinities with Voegelin, he exhibits them again with Father Seraphim Rose (1934 – 1982), the American Greek-Orthodox diagnostician of modernity. Venner’s critique of nihilism runs strongly in parallel with Father Rose’s, as set forth in the latter’s little volume, Nihilism: The Root of the Revolution of the Modern Age (1994). Passages from Venner could be inserted into a chapter by Rose and no one would notice; and ditto the other way around. Both men are apt, for example, to quote Nietzsche with approval. Here is Venner on nihilism:

Jünger has suggested that, to represent nihilism, it is less necessary to picture bomb-throwers or youthful activist-readers of Nietzsche than it is to picture ice-hearted high functionaries, either academicians or financiers, in the exercise of their offices. Nihilism is in effect nothing other than the mental universe required by their calling, that of rationality and efficiency as supreme values. In the best cases, [nihilism] manifests itself by the will to power, and, more often, by the most sordid of trivialities. In the world of nihilism, everything is subject to utility and desire, in other words, to that which is qualitatively inferior.

Venner continues with a long additive iteration: “It [nihilism] is the world of applied materialism, of nature transformed into garbage, of love travestied as sexual consummation, of the mysteries of the personality explained by the libido, and those of society elucidated by the class struggle, of education tuned into a factory of specialists, of the morbid glut of information substituted for knowledge, of a backwards politics made subordinate to the economy, of happiness brought down to the level of mass tourism, and, when things turn bad, the slide into violence without brakes.” And here is Rose on nihilism:

Nihilist “organization” – the total transformation of the earth and society by machines, modern architecture and design, and the inhuman philosophy of “human engineering” that accompanies them – is a consequence of the unqualified acceptance of industrialism and technology which… must end in tyranny. In it we may see… the transformation of truth into power. What may seem “harmless” in philosophical pragmatism and skepticism becomes something else again in the “planners” of our own day. For if there is no truth, power knows no limit save that imposed by the medium in which it functions, or by a stronger power opposed to it.