In praise of Ray Bradbury

Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles are thoughtful meditations on the nature of human existence. They are easy to read and fun to use in an ethics class for that reason. One of the stories is named after the Sara Teasdale poem, There Will Come Soft Rains. Apparently written in response to the German ground offensive of WWI in 1918, and during the flu pandemic, the poem states that nature, in the form of birds, frogs, and trees would not notice our absence. And “Spring itself,” barely so. The implication is that human beings lie outside nature, although “Spring” seems to have some dim sense that we exist. There is no mention of God, who might be presumed to miss us. Teasdale had apparently developed the nihilistic view that the universe cares not at all about our actions or existence from reading Charles Darwin, starting in 1913. This is the same erroneous notion that Richard Dawkins likes to promote. It is a view that pushes human beings outside the universe, which is incorrect since parents are in fact part of the universe, and they generally love and care for their children. Human babies are so dependent on mothers that they would all die without this beneficent parental orientation. The problem is not with human beings, the universe, or nature, but with atheism which leads to moral nihilism if followed consistently, as discussed below. It is not only human beings who lose their intrinsic value and significance under atheism, but nature, too. Crude materialism reduces “nature” to mechanistic forces blindly ramming into things in deterministic fashion. Without a telos, in the manner of Aristotle’s Prime Mover, attracting creatures to ascend from their potential form to their actual form via moral aspiration, drawn to the perfection that God represents, things happen at random, teleologically speaking, with no underlying meaning.

Unlike Darwin, modern and up-to-date evolutionary theory, as seen in Perry Marshall’s Evolution 2.0, sees living cells and organisms engaging in horizontal gene transfer, transposition, epigenetics, symbiogenesis and hybridization. The levels of intelligence and teleological (purposeful) behavior is truly astounding.

It is human poetry that teaches and reminds modern man to see “nature” as something beautiful and worth preserving. Primitive man did it instinctively, but we moderns frequently have to work at recovering and maintaining such a vision. It is partly a matter of how much time we spend indoors. Put in the right context; by the sea, in a forest, hiking a mountain, we can fairly easily appreciate natural beauty once again.

Ray Bradbury’s short story serves as a rejection and criticism of Teasdale’s poem. In another story, And the Moon Be Still As Bright, named after another much better poem by Lord Byron, Spender discovers that the now defunct Martians managed to combine religion and Darwinian evolution, without thinking they were antagonistic, and that this was a great achievement we humans could learn from. As such, Bradbury has read his Darwin, but did not find himself sucked into atheism or nihilism. Bradbury’s There Will Come Soft Rains contrasts the events in an anthropomorphized house after a nuclear conflagration has vaporized its inhabitants, with the Teasdale poem. His story displays real affection for humans, their hobbies, sources of enjoyment, artistic production and appreciation, imagination and creativity; second to none in nature. The house unfolds card tables and sets them, pours martinis into glasses, produces egg sandwiches, and plays recorded music. After children’s hour with their hot baths run, and dinner time, a cigar appears next to a blazing fire. Reading these descriptions of bygone modes of living, has its own poignant sense of a lost time. Walls come to life in the children’s rooms, depicting wild animals, though of unnatural colors; in their settings. This can be seen as representing the human capacity for appreciating the beauty and interest of other parts of nature, with an element of fantasy. If nature lost its humans, it would lose a creature capable of appreciating her. Beauty unnoticed is, to a degree, wasted.

Bradbury writes: “The house was an altar with ten thousand attendants, big, small, servicing, attending, in choirs. But the gods had gone away, and the ritual of the religion continued senselessly, uselessly.”

Killing all humans would recapitulate the death of God. With the failure to believe in a Creator with a purpose, the universe lost much of its perceived meaning. With the death of humans who were made in the image of God, with some of God’s creative capacity, reason, and love, the significance of the universe would recede yet further. Those who remembered the living God would themselves be killed off and forgotten. The singing of the birds may be their prayers to God, at least to the minds of poetically minded humans, but they are missing the same level of depth and complexity.

While not being capable of writing a Ray Bradbury story, one can at least appreciate it. Stories live in human consciousness. Ink on pages, or pixels on a screen, are only potential stories that need to be realized and animated by our minds. Beautiful and poignant stories like the story There Will Come Soft Rains will no longer exist when there are no humans to read them. Likewise, while Teasdale seems fine with nature not missing self-destructive humans, her own poem depends on humans for its existence and meaning, too. Being a parent reading to a child, especially of stories enjoyed in one’s own youth, represents a lovely mixture of cultural transmission, sharing one’s loves with another, and mutual engagement in an imaginative activity.

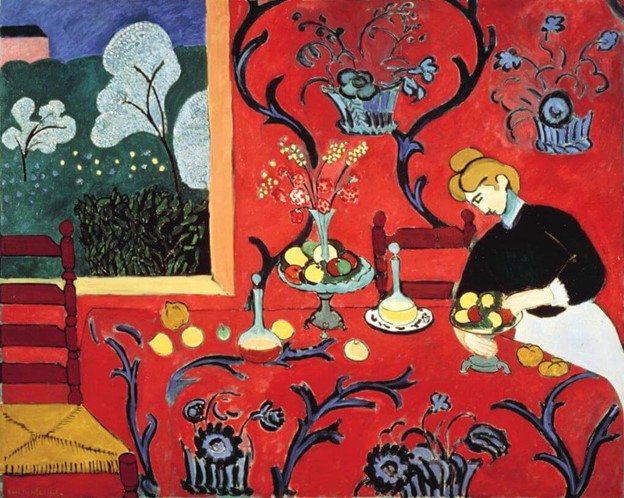

The fire that envelopes the house, brought on by a wind that blows over a tree that hits the building, burns up Picassos and Matisses. Exemplars of fine art, and a vision that transfigures the world, represent what would be lost without humans. No creators and no appreciators. Animals, needless to say, are oblivious to paintings.

The stove cooks breakfast that no one is there to eat. The food grows cold and is disposed of down the sink. The food is wasted as is the effort in cooking it. This continues the theme of sadness and loss, not the nonchalance of an unfeeling nature. The dog is lost without its masters for food and company and dies horribly. The wall announces a birthday for the household to remember; again, death and loss, rather than Teasdale’s oblivious nature. At the end, a voice within the wall repeatedly announces the date and time, acting as a speaking tombstone for those people it was designed to hear it. The story gives an inkling of what would disappear when we do.

Some students, the same ones who did not notice that Bradbury is rejecting the message of the Teasdale poem, have adopted the position that the existence of human beings is a cosmic and moral mistake and that they should all be eliminated. This nihilistic and hateful view is supposed to be motivated out of love and concern for the natural world which human beings negatively affect by their presence. Gone are the injunctions to love your neighbor as yourself, or to do unto others as you would have them do unto you. They are replaced by hate your neighbor, as he hates you. Do not do unto others as you would have them do unto you, but wish for your neighbor’s destruction and disappearance as he wishes for yours. This violates reciprocity and justice. You may think the planet should be rid of human beings. What of those of us who wish no such thing? What if you are wrong, which you undoubtedly are? Wise, loving, and happy are not adjectives that come to mind with regard to someone who adopts this view.

Taking advice from someone who hates and despises himself is not a good idea, let alone someone who hates and despises you. For such a momentous decision affecting everyone, wisdom is an absolutely necessity. Nobody in his right mind would consider someone who clubs people to death “wise.” One climbs a mountain to consult the loinclothed wise man and he shoots you in the head. A fairly cross-cultural notion is that life is a gift to be cherished and used wisely. No wise person would side with the alien destroyers from The War of the Worlds.

It is crucially important for the human eradicationist to be right. Once humanity has been eliminated, there is no going back. Humans have no great track record of being right about things. The scientific revolution introduced a mechanistic worldview, for instance, that was probably a really bad idea, since it included how we viewed human beings. Before going along with the judgment of the student, we should ask if he is a successful, flourishing human being for whom things are going well? Or, is he perhaps bitter and resentful? What sort of moral standing and wisdom could possibly exist to make this irreversible decision for everyone?

By definition, the human eradicationist is antisocial; low in agreeableness and conscientiousness. The former measures, in comparative terms, how much someone cares about the thoughts and feelings of others. While sometimes useful – geniuses have to be antisocial in order to deviate from the crowd and so that they do not care that their discoveries are disruptive – on this particular topic, an antisocial person is the wrong person to ask.

The student who wishes to eliminate all human beings has gone beyond the concern for police shootings, social justice, and all the rest, promoted by our current elite, and has adopted the view attributed to Cthulhu. No Lives Matter. Cthulhu is an invention of H. P. Lovecraft who wanted to create a creature who could horrify atheists. Theists, by definition, must be amenable to the supernatural and so might be able to countenance angels and demons. Lovecraft wanted a picture of horror that even an atheist could feel.

It seems highly doubtful that love has anything to do with wanting to eliminate humans for the sake of “nature.” Is the person a great outdoorsman? Is he knowledgeable about the rest of nature? From whence comes all this “love?”

Since nature and evolution gave rise to sentient beings capable of self-awareness and to polluting the planet, the human eradicationist must hate all of nature and evolution, too. It makes no sense to defend and “love” something that produced we “evil” human beings. To love nature, is to love humanity. We are part of nature. Therefore, a consistent human eradicationist must wish for the end of nature, too. What if some other intelligent creature evolves to take our place? What should happen then? Should we perhaps destroy the world to prevent this from happening? If even the tiniest cell remains, which it undoubtedly would, then evolution could simply recapitulate what has happened once before.

The human eradicationist has failed to love humanity or any of its cultural or spiritual achievements. He has proved supernaturally insensitive to human creations. It seems likely that this deadness of soul will permeate his entire existence. To commit Bach, Mahler, and others to the flames, to wish that Dostoevsky and Tarkovsky, the Hudson River School, Plato and Plotinus, Newton and Einstein, Wordsworth and Machado, Andrei Rublev and Michelangelo, Shakespeare, Homer, the Greek tragedians, Buddha, Jesus, and Socrates had never existed, is a triumph of hate and spiritual imperviousness. Of course, the reader should substitute his own favorite exemplars of human genius.

Gnosticism posits that the earth was created by an evil Demiurge and that all creation is evil. A creation that gives rise to human beings should qualify for the eradicationist. It is true that only a human being could be evil enough to wish that all of its own species were exterminated, but such people are not representative of humans as a whole.

There are just two main live options when it comes to metaphysics – which involves ideas about the ultimate nature of reality. The theological and the materialist. A crude materialist dissolves all reality down to atoms and molecules, or, if he is particularly erudite, modern, and with it, quantum foam and the like. Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things provides an early template for this mode of thinking, making him the Patron Saint of modern-day materialist nihilism. If that sounds odd, Richard Einhorn wrote an oratorio for Charles Darwin. This parody of religiously inspired devotional music was enthusiastically performed here in Oswego many years ago, with choral members singing his praises, atheists among them.

Once reduced to the atomic level, of atoms banging into each other, a picture is created of a dead universe filled with denuded rocks spinning through a cold, indifferent space. This is where Richard Dawkins draws his erroneous assertion that we live in a loveless, uncaring universe, as did Teasdale. It sounds like Dawkins’ parents have something to answer for. An orphan, perhaps, could understandably feel such a sentiment.

Atomic materialism cannot have evolution, life, or morality. It is too stunted and limited. There can be no physicists in such a world. Anything above the level of the complexity of those atoms is regarded as null and void; never mind the existence of minds necessary to contemplate this mess.

So, if we are going to discuss whether human beings should exist or not, which really should not be necessary, we will need to break away from this bleak vision – a reality where “vision” has no place – and climb all the way up to the level of biology, passing through chemistry on the way. This level of complexity is rhetorically necessary just to talk about human beings at all. Atomically, they are indistinguishable from their surroundings.

For the Ancient Greeks, the eradicationist view is related to that attributed to a god/satyr, “wisest, oldest, and drunkest,” companion and tutor of Dionysus, Silenus, who saw we mortal humans as subject to misfortune and “whose life is but a day.” Upon being captured and pressured by King Midas to tell him the meaning of life, Silenus warned Midas that he would not like the answer: “Best is never to have been born at all, but the second best is to die soon.” This was not, however, connected to “nature” being better off without us.

This despairing nihilism has surfaced in modern form with “The Voluntary Human Extinction Movement,” led by the execrable Les Knight; our knight in shabby armor who has not come to rescue us but to bury us. Benighted, indeed. Both The Guardian and The New York Times have featured him prominently and approvingly. As gatekeepers and purveyors of regime propaganda they would simply not mention him at all if they did not like his message.

Corresponding to the two live metaphysical options, there can be just two things underpinning arguments for or against the eradication of humans; religion or biology. Neither point of view can possibly justify voting the human race off the planet.

If God exists, then the human race and all of creation is considered good as stated in Genesis. Our existence is the product of the divine purpose. We might argue about what exactly that purpose is, but, if there is a God, some purpose there must be. Second guessing God and claiming that he made a mistake in creating human beings is understandable when undergoing some particularly traumatic circumstance, or when suffering from severe depression, but there can be no theological justification for this claim.

The existence of God is necessary to make free will possible. And, relatedly, for moral realism to exist. Moral realism is simply the idea that good and evil actually exist, and they exist independently from any particular customs and conventions any specific society might adopt. Human ideas about morality are distinctly fallible. Moral truth and the axioms of morality, however, are not dependent on whether we correctly perceive them or not. The truth and goodness of reciprocity is as real and indisputable as any mathematical truth. It is true that a psychopath cannot perceive this truth, just as the innumerate cannot perceive or understand mathematical truths. Treat others as you would have them treat you, supported by appropriate caveats, simply makes sense. It is only fair. The caveats are that one cannot simply take one’s own preferences and desires and treat other people as though they have exactly the same preferences and desires. One must treat other people in such a way that you take into account their preferences and desires, just as you hope that they do to you.

Materialist metaphysics cannot accommodate free will, or make sense of it, so it also cannot make sense of morality. No one is morally responsible for actions that he had no choice but to perform. In fact, without free will, there are no “actions” at all. Only events. “Actions” require agents – centers of decision-making – and agents do not exist for a consistent materialist.

A love not connected to free will is irrelevant, and meaningless. A compelled love has no value. If the human eradicationist does not believe in God, then their own supposed “love” for the natural world divorced from humans is an accident of physics. It is an involuntary result of happenstance scientifically described events of no significance whatsoever. There is no reason to act on this nonlove.

Ivan, in The Grand Inquisitor section of Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, indicts God for allowing the torture and maltreatment of innocent children. He argues that free will means that such things can occur, but that hurting children is particularly unfair because children are not really capable of free will. They are too young to be credited with true moral responsibility. So, they become the victims of the actions of adults, who exercise their free will in doing so, while children do not benefit from free will themselves. However, since meaningful love and morality only exists if free will is real, then Ivan is using the very morality and love for children that the existence of God makes possible, to critique God. His criticism depends on the very thing that his criticism condemns, standing in judgment upon God and using God’s own criteria against him. As such, Ivan’s criticisms are unintelligible. If he got what he wanted, the elimination of God and his conviction, he would be unable to make his points. The same free will that makes harm to children possible, also makes it possible to love them.

Materialists might say that morality, although an illusion and untrue, is nonetheless useful – meaning it has extrinsic value: value as a means to something else. However, extrinsic value is parasitic on intrinsic value and there is no intrinsic value without God and the divine. Being made in the image of God gives us the same intrinsic value – value that is good in its own right as happiness is – as God. The divine transcendence introduces something nonnatural into the materialist picture, along with souls, beauty, love, consciousness, purpose, meaning, and all the rest. “Science,” the study of material reality, cannot find any of those things and cannot locate “value” either. Value is not a scientific category. It might help tell us if something is indeed a means to an end, and thus has extrinsic value, but thinking of it as “value” is something we humans perceive, but not humans qua (in the capacity of) scientists.

Humans being made in the image of God gives us a value derived from the supernatural and it makes us both sacred and possessed of intrinsic value.

In Why God and the Person Must Be the Highest Ideal it is stated, accurately and more or less tautologically, that any theory of morality that puts anything other than the Person as the highest ideal is inherently sacrificial. It will sacrifice the Person at the altar of some other highest good such as environmentalism, feminism, social justice, diversity, anti-colonialism, etc. Any other highest good is announcing its desire and willingness to torture, murder, and otherwise dispose of the Person in the name of some higher ideal. If the person reading this disavows such behavior, then he has reinstated the Person as the highest good. And the position that the planet would be better off without human beings and that it would be a good thing if we went extinct is an obvious example of sacrificial thinking.

So, there can be no morality without religion. There can be conventions and customs without religion – although even how long those will last is another question – but there can be no morality in the sense of moral realism. So, there can be no moral argument in favor of human extinction, yet, this is exactly what those who argue in favor of human extinction think they are doing.

Atheist scientists have attempted to found morality on biology. It cannot be done, as demonstrated in Darwin vs Morality 1, and Darwin vs Morality 2, and Can Evolutionary Biology and Naturalism Provide the Basis for Morality?. They can show that morality can provide some survival and reproductive benefits to a person and to a society, but “survival” may or may not be consistent with morality, depending on the circumstances. What happens each time is that full moral realism gets illicitly added to the argument, usually towards of the end. For instance, Richard Dawkins thinks that the reputational benefits of being a morally good person cannot survive the transition to a larger community where people are relatively anonymous, but then he declares that this “mistake” in continuing to do good things for people is a morally good thing. So, on the one hand he says that morality is there to confer reputational benefits, and that is why it is good, but once those benefits stop, it is still good! This makes no sense. Presumably, his readers do not notice this fallacious thinking because they are sympathetic to both atheism and morality and want them to be compatible. They are not.

So, the human extinction proponents do not have a leg to stand on. They think that the degradation of the environment caused by human beings is a morally bad thing, and they propose to solve this problem by eradicating human beings. But, moral realism only exists if God exists, and if God exists, it cannot be that human beings should not exist. We are made in the image of God and are part of His divine purpose.

Biology has no moral categories or values and so cannot be used to make moral arguments in favor of exterminating humanity. Biologically, what organisms want to do is to survive and reproduce. Asking an entire species to kill itself has nothing to do with the dictates of biology. Any species with the urge to die and to fail to reproduce would never have existed in the first place. If we appeal to biology, then biology says, “Live. Go forth and prosper, and reproduce your kind.”

So, having eliminated morality or biology as the basis for calling for human eradication, we can turn to what sort of person might be tempted to think that human extinction would be a good idea. Given that there are no legitimate arguments in its favor, it is time for diagnosis. In morality, we have ingroups and outgroups. Ingroups include those who fall within our sphere of moral concern. Outgroups are those for whom we morally do not care. The human eradication proponent and enthusiast has deemed the entire human race as an outgroup. Thus, he identifies with the nonhuman plants and animals. Antihumanity, AKA misanthropy, is the ultimate outgroup identification. Such a person is a traitor to all humanity. The sort of person who feels this way must feel completely alienated from his fellow human to the point of wanting to disassociate himself from all people, to have all human beings disappear from the planet, and this requires extreme negativity towards the human more than love of the nonhuman. This kind of alienation requires extreme neuroticism – which involves feeling negative feelings very strongly. Negative feelings include alienation, sadness, anger, resentment, jealousy, hatred and all the rest. One can love the natural world, with its plants and animals, without wishing for the death of humans.

It would be interesting to see what kind of real love for plants and animals the human eradicationist shows. Genuine love of the nonhuman would be demonstrated by going and “living in nature.” By taking active steps to rescue, help, and protect wild animals and plants. It seems likely that the human extinction advocate has done nothing of the kind.

If it is all talk and no action, then the human eradicationist is virtue signaling. He is hoping to convince his fellow human that he is more moral than them. The neurotic hater of humanity is using supposed sympathy and compassion for the outgroup, with whom he identifies in his alienation, against his own ingroup, whom he hates. White people who hate other white people and who identify with nonwhites do the same thing. If there were justice in the world, such people would directly suffer for their beliefs. However, this is not the case. They use their outgroup identification to promote their own careers and to show just what a supposedly good, moral, and compassionate person they are. “Beware white progressives bearing gifts.” The gift is poisonous. They do not really care about what is in the best interests of the outgroup. They do not think they can compete honestly and directly, because they are insecure and neurotic, so they do it dishonestly and indirectly. They have no skin in the game. What cost are they paying for their position? Nothing. Quite the reverse.

The human eradicationist must think that his own existence is a mistake, as is his parents, friends, and community. He looks with hatred and malice at every person he has ever met and known. He is the teenager who screams, “I hate you all.” The one who pictures her own funeral and says, “You’ll be sorry when I’m dead.” He cannot and should not be trusted.

It would be interesting to know how much the human eradicationist actually knows about the lives of wild animals. Does he know that bears, for instance, do not kill their prey before eating them? They just start tearing chunks of flesh off the screaming animal. Big cats, conversely, smother their prey first. Better to be one of their victims. In fact, the whole of nature has been described as a charnel house[1] of murder and mayhem; of prey and victim. Though, this is an incomplete picture that omits cooperation between animals, and the maternal love seen in birds and mammals.

Once all the humans are killed and gone, so is all morality, though some of the higher primates have some proto-morality, and rats demonstrate ingroup behavior towards others.

What makes human beings most lovable and worthy of preservation are our finest achievements in music, art, philosophy, science, literature, and architecture. Some of those things require a deep cultivation of the self in order to appreciate. This is going to be rare. The human eradicationist can be predicted not to love any of those things, nor to having spent a lot of time admiring and appreciating them. Nor, to be capable of any such love. The human eradicationist will almost necessarily be a philistine, immune to the beauty and grandeur of the achievements of the past (the future not yet existing). Most people are mediocre. The most that we can offer of value, is to value the products of genius. If one is a teacher, the best thing you can do is to pass on this love to those of your students who are capable of sharing it.

Lastly, human beings represent the universe coming to conscious self-awareness, to the point that the universe turns around and studies itself. Killing us would be to put the universe back to sleep, never to wake up. We may be the only creatures in the universe who have reached that level of cognitive and emotional sophistication. The beauties of the natural world will no longer be appreciated with as much depth of feeling and subtlety as the finest human minds and hearts. No animal will write poetry in praise of it, nor read stories to their children embodying the insights and sentiments of the most sensitive writers.

Aristotle pointed out the continuity and differences humans have relative to the rest of nature. We have a nutritive soul, like plants and animals, enabling us to take in nourishment. We have a sensitive soul, providing feelings of pleasure and pain, and desire to favor pleasure. This also enables locomotion. And, humans, in addition, have a rational soul, enabling contemplation and practical wisdom.

A frontal lobotomy would remove a fair amount of pain and suffering from an individual, but it would also eliminate what is most remarkable and praiseworthy. To visit an alien planet and to kill its most intelligent species would be a moral travesty and disaster. To do the same thing to this planet, would be the same. At this point in time, we know of no other place in the universe where consciousness exists, nor where the universe has attained self-consciousness. To wish to remove it, is an act of total nihilism. And to use the rhetorical assertion that this would be good thing in order to improve one’s own status within one’s group is truly morally disgusting. It is a view that only an atheist could espouse – though, fortunately, this does not mean most atheists would.

[1] A building or vault in which corpses or bones are piled. A place associated with violent death.

I have heard it said that it would be better if humans were exterminated. It is odd that extermination of the species can be discussed with a pretense of moral seriousness, while anyone who discusses extermination of a subset of the species is the worst sort of moral monster. I’m sure there are university courses in which elimination of the species is discussed as something with much to be said in its favor. I’m just as sure discussions of genocide are completely one sided. I think I once told you that I long ago founded a minor academic journal devoted to environmental ethics, but eventually gave up the editorship because so many of the papers we published we profoundly misanthropic.

You’ve very well stated the essential problem with making the world better through human elimination on materialist grounds. The would would not be better once the last human was gone because “better” would be gone as well. Beauty also.

In practical terms, the argument for extermination of the species is genocidal. One can see it as a Darwinian bottleneck or as a conspiracy, but the argument does not affect all humans equally. Some will fall under its evil spell and remove themselves by infertility, or in some cases suicide. Others will laugh at the absurdity and inherit the earth.

Very interesting. Thanks, JMSmith. The combination of, say, “safe spaces” and genocidal fury is most bizarre and likely to be expressed by the same people.

While I’m sure the wrong combination of the Big 5 contributes to these genocidal fantasies, how many of these types developed a burning hatred of humanity due to being abused, bullied, humiliated, etc. Monsters are kinda born and made, right?

Have you ever met a misanthropic animal lover? I am related to some. People have done them wrong so they hate mankind and love pets (who don’t hurt or betray you).

Hi cameron232

That all sounds possible and likely. However, the article is really directed at those who have picked their misanthropy up from popular culture. Those are the ones I’m worried about, similar to anti-natalism with its mimetic basis.

Pingback: Summary of the W!tchy War on Masculinity | Σ Frame